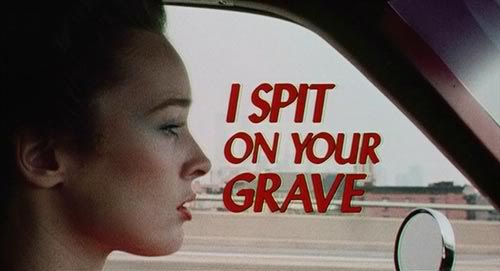

Day of the Woman

Of all the films I have elected to discuss here at The House of Glib, today’s is BY FAR the most controversial. Few films in the brief history of the art form have managed the nearly impossible trick of being praised by some as a low-budget masterpiece of feminist cinema, while also being denounced by others as the worst example of misogynistic exploitation trash ever to be devised by a truly sick and twisted mind. While serving as a perfect case of how much a film’s title and marketing can influence an audience’s reaction, today’s film is important for also forcing the viewer to ask themselves how far is too far when it comes to getting a desired point across. At what point does a filmmaker cross the line from exposing society’s evils to exploiting them? And should they be blamed if certain segments of the audience respond to the material in the exact opposite way that they intended?

For those reasons today’s subject is the rare example of a film whose content makes it almost impossible to recommend to others, while also being one that no serious student of the filmmaking arts can justifiably avoid—it’s a film that should be shown in every introductory film class, but never will be because of the protests its inclusion would inevitably engender.

I am, of course, talking about:

Originally released as Day of the Women in 1978, Polish sound editor Meir Zarchi’s directorial debut was inspired by a real life incident in which he and a friend discovered a badly beaten and nude woman who had been raped in a park near his home. Not only had he been horrified by the barbarity of the woman’s attackers (they had broken her jaw and only allowed her to live after she insisted that there was no way she could identify them since they had smashed her glasses and she could not see their faces), but also by the terrible bureaucratic indifference of the police officer who took her report and seemed far more concerned with getting it finished than calling the ambulance she so obviously needed. To Zarchi’s eyes the casual cruelty of the apathetic officer was little different than the animal savagery of the rapists and in the years that followed the incident he began to imagine a film in which a woman survives a terrible rape, but instead of going to the police for justice, decides to take the matter into her own hands and forces her attackers to understand how terrifying it is to be a victim of another person’s remorseless brutality. He wrote the screenplay during the 40-minute subway commutes to and from his New York office and was able to raise enough money (and defer enough payments) to make the film with a cast of unknowns and a crew largely composed of enthusiastic amateurs.

The film begins in New York, but only stays there for the briefest of scenes. Jennifer Hills (Camille Keaton), a successful young short story writer has decided to leave her apartment in the city in order to enjoy the peace and tranquility of a lake house located in rural Connecticut, where she plans to write her first novel. On her way there she stops for gas at the town’s antiquated station, where the attendant, Johnny (Eron Tabor) takes notice of her sophisticated beauty, while his two dimwitted friends, Andy (Gunter Kleeman) and Stanley (Anthony Nichols) play a game that involves throwing a switchblade into the grass at their feet.

Upon reaching the lake house, Jennifer is so excited by the quiet, natural beauty of her surroundings that she runs towards the water and takes off her dress and enjoys a naked swim in the water—visibly thrilled to have escaped the noise and squalor of the city.

We next see her as she unpacks her clothes and discovers a gun left behind by a former tenant in one of the drawers, but before she can do anything more than look at it, she is interrupted by the sound of someone knocking on her door. It turns out to be Matthew (Richard Pace), the Lenny-esque manchild who works as the delivery boy for the local grocery store. When he learns that she’s from New York City, he tells her that she “…comes from an evil place!” She humours his small-town innocence by giving him “…a tip from an evil New Yorker,” which he excitedly tells her is the largest he’s ever received (a whole dollar). He’s also becomes excited when he learns she’s a real writer and is famous (even though he’s never actually heard of her) and—as he chomps on an apple she gives him—he asks her if she has a boyfriend.

Thrilled by his encounter with the glamorous woman from the big city, Matthew leaves and finds his friends—the same three men Jennifer encountered at the gas station. Trying to impress them he tells them that he “…saw her tits!” (referring to the fact that she wasn’t wearing a bra underneath her shirt). It’s obvious that they aren’t a good influence on him, but they’re also the only people around who treat him like an equal—largely because they’re not that much smarter than he is. Having exhausted all of the other diversionary activities their small town offers, the four of them decide to go fishing. There they discuss whether or not beautiful women have to defecate (they decide that they do, since all woman “…are full of shit”) and how they have to get Matthew “…a broad…” to rid him of his virginity. Stanley takes a shot at Matthew’s sexuality by claiming that, “…broads don’t turn him on!” to which Matthew responds by insisting, “Yes they do, but not all broads, only the special ones.” Johnny humours him by asking, “What’s a special broad, Matthew?”

“Miss Hill,” answers Matthew. “Miss Hill is special.”

Unaware of the impact she is having amongst the locals, Jennifer continues to commune with nature by going on canoe rides and sitting outside as she writes out chapters of her novel in long hand on a yellow legal pad. Her peace does not last, however, when Andy and Stanley drive by on their motorboat. Intent on getting her attention, they obnoxiously loop around the water until finally she has no choice but to go inside in order to escape them.

Later that night, while she is alone in bed, she is disturbed by the sound of clearly manmade animal noises coming from outside the house. She goes outside to see where they are coming from, but sees only the darkness of the night and decides to go back inside, where she reassures herself with the knowledge that she has the gun she found in the drawer, if she needs it. It turns out that she soon will, but at a time and place where no one would think to bring it.

During the middle of a hot summer day, Jennifer basks in the rays of the sun as she lies out in her canoe as it floats across the water. Her calm does not last long, though, as Stanley and Andy return in their motorboat. This time, however, they intend on doing more than simply show off. They begin by driving around her canoe, causing it to shake in the waves, and then they grab its rope and begin pulling it behind them. They take it to the shore, where Jennifer tries to fight them off with her paddle, but they quickly get it away from her and begin chasing her through the woods.

Jennifer soon discovers that this attack was planned when she reaches a clearing and is knocked down by Johnny, who has been waiting for his two friends to deliver her to him. With Andy and Stanley’s help he tears off her bikini, holds her down and urges Matthew to come out from his hiding spot and take what they had gotten for him. Matthew, torn between his loyalty to his friends and his affection for Miss Hill, refuses to rape her, but agrees to hold one of her legs as Johnny decides to do what he won’t. Johnny strips out of his clothes and roughly penetrates Jennifer.

When he finishes, his three friends let her go and they all watch as she crawls away into the woods. Johnny sends Matthew out to get her back, but he just helps her up and watches as she limps away. The others taunt him for not taking advantage of the situation, with Johnny telling him, “…You’re gonna die a virgin.”

Naked and barefoot, Jennifer is forced to walk through not only the forest, but also small streams and swamp water in order to get back home. Sadly, though, her attackers know the area far better than she does and are able to find her again. This time Stanley rapes her—sodomizing her as Andy and Matthew hold her down on a large rock. He climaxes as quickly as Johnny did and the four of them leave her stretched out on the rock and return to their boat. Making their escape they abandon her canoe in the middle of the lake and Johnny throws her bikini into the water.

Bruised, bloodied and covered in mud, a nearly catatonic Jennifer is finally able to get back to the lake house. Upon reaching it, she collapses and has to crawl in order to get to a shirt to cover her naked body and to then get to the phone to call the police.

But her attackers are not done with her. Just as she finishes dialing, the phone is kicked away from her and Johnny appears at the top of her stairway. As the others cheer him on, a now-drunk Matthew overcomes his shyness and strips naked and jumps on top of their victim, but isn’t able to finish like the others. As he dejectedly puts his clothes back on, Andy finds some pages from Jennifer’s unfinished novel and reads them aloud for everyone’s amusement before he tears them up and throws the ripped up pieces on top of her.

The other three having had their turns, Stanley is the last of the four to take advantage of their captive. Jennifer—knowing that she can’t stop him and has been badly hurt by the other’s rough penetrations—begs him to allow her to fellate him instead. “Total submission, that’s what I like in a woman,” he sneers just before he sadistically shoves a bottle into her vagina and orders her to perform oral sex with the command “Suck it, bitch!” Unhappy with her lack of effort, he gets up and starts kicking her, which—despite their previous barbarity—is too much for even his friends to take. They pull him outside and start to leave, but then Johnny decides that they can’t leave her alive after what they did to her. He hands Matthew a switchblade and tells him to go back inside and kill her. Matthew naturally refuses at first, but Johnny is finally able to convince him to do it. With the knife in his hand he returns inside the house, where Jennifer is laying unconscious on the floor. He puts the blade to her chest, but he can’t go through with it, so he instead wipes it across her cheek, covering it in blood, which he shows to his friends in order to prove that he did it. Assuming that they now have nothing to worry about, the four of them escape away from the house down the water in their motorboat.

Knowing that there is nothing the law can do to get her the justice she deserves for what the four men have done to her, Jennifer does not call the police. Instead she slowly nurses herself back to health and picks up the pieces of her now-shattered life. One day she spots her canoe floating in the water outside of her house and is able to retrieve it. The next she spends patiently taping up the pages from her novel that Stanley tore up in front of her and soon she starts writing new pages to go along with them. The days pass by and her visible wounds fade, leaving only the ones left on the inside—the ones she’ll have to eventually leave the lake house to cure.

As their victim convalesces, the four rapists grow concerned that she might still be alive since they had not heard any news about her body being discovered by the police. Johnny attempts to convince Matthew to go to the house to check, but he refuses and it’s left up to Andy and Stanley to find out for sure. They drive past the house on their motorboat and see their victim sitting at a tree reading a book. Knowing now that Matthew lied to them, the three others beat him up and make it clear that their friendship is over.

As the quartet self-destructs, Jennifer is finally ready to open the drawer that holds the gun she found her first day there. Dressed in black, she drives to the local church and asks God to forgive her for what she is about to do. She then drives to the gas station where Johnny works, but stops herself from carrying out her plan when she sees him with his wife and children. She then spots Matthew as he rides past her on his bicycle and decides to begin with him.

She returns home and places an order to the grocery store where he works. Upon being told of the address of his next delivery, Matthew gets scared and steals a knife from the meat counter to protect himself. When he arrives at the lake house, he finds Jennifer waiting for him outside, dressed in a white robe that makes her look like an angel. He follows her into the woods, holding up the knife he brought with him—ready to use it if he has to.

With the knife in his hand, he finds her standing beside a tree next to the water.

“I hate you! I hate you!” he cries at her angrily.

“What have I done to you Matthew?” she asks with an eerie calmness that almost borders on kindness.

“I have no friends now because of you!” he tells her.

“Why, Matthew?” she asks as she begins to untie her robe. “Why because of me?”

“Because I was chosen to kill you and I didn’t!”

“You will this time Matthew,” she says encouragingly. “You will. Just relax.”

“I’m sorry I have to do this,” he apologizes. “I’m also sorry for what I did to you with them. It wasn’t my idea. I have no friends in town.”

“I thought we were friends. Remember? You asked me.”

“You’re only here for the summer! What am I to do the rest of the year?”

“I could have given you a summer to remember—for the rest of your life,” she tells him as she pulls apart the robe and exposes one of her breasts.

With the knife still raised above his head, she shows him the rest of her naked body and pulls him in for a kiss. She then kneels down and takes off his pants and pulls him on top of her. As he has sex with her (doing now what he earlier could not), she reaches behind to a noose hidden in the leaves of the tree and slips it around his neck. She then starts pulling on the rope the noose is attached to and lifts Matthew up into the air, his body jerking spastically as he slowly suffocates. She waits until she is sure that he is dead before dumping his body and bicycle into the river. She then returns to the house and calls the grocery store to inform them that her delivery never arrived.

Having taken care of Matthew, she decides it’s time to return to Johnny. She finds him by himself at the gas station and is able to wordlessly convince him to get into her car—using nothing more a flirtatious look and a nod of her head. She drives him to a clearing, where she pulls out her gun on him and orders him to strip. Johnny does as he’s told, but rather than beg for his life he explains how what happened was really all her fault—insisting that she provoked them with her sexy clothes. Jennifer allows him to believe that she is swayed by his reasoning and hands her gun over to him and invites him back to her house. He agrees—not realizing that she is only doing so in order to make him suffer much, much more than he would have if she had just shot him.

Back at her house, she joins Johnny in her bathtub for a bubble bath as he complains about his wife and friends. He tells her that Matthew is missing, but that he’ll probably turn up sooner or later.

“He’ll never come back,” Jennifer tells him as she massages and caresses his chest.

“Why, do you think he committed suicide or something?” asks Johnny.

“No,” she answers matter-of-factly. “I killed him.”

Despite her protestations to the contrary, Johnny refuses to accept that she isn’t joking and doesn’t see it coming when Jennifer reaches for a knife she has hidden underneath a towel and uses it to castrate him. Her rapist is so relaxed in the water he doesn’t even realize it has happened until he sees the water turn red. Jennifer calmly gets out of the tub, puts on her robe and locks Johnny inside the bathroom as his cursing turns to begging for help and mercy. She drowns out his cries by playing an aria from Puccini's Manon Lescaut.

This just leaves Andy and Stanley, who—knowing that both Matthew and Johnny are missing—suspect that their own lives are in danger. Stanley approaches the house on his boat, while Andy comes by land—armed with an ax. Jennifer, swinging in her hammock in a green bikini, hears Stanley coming and surprises him by swimming to his boat and climbing in.

“Where’s your friend?” she asks him.

“He stayed back in town,” he lies to her.

“I’m glad,” she lies right back to him. “It’s you I wanted.”

As clueless as Matthew and Johnny, Stanley leans in for the implied kiss, which gives Jennifer the opportunity she needs to push him out of the boat. As he splashes in the water, she starts the motor and starts terrorizing him with the boat just like he and Andy did to her before. Andy reveals himself from where he was hiding on the shore and screams at her to leave his friend alone as he climbs into the water. Using the boat, she manages to steal away his ax and watches as Andy swims towards Stanley in a foolish attempt to rescue him. The two of them attempt to make it to shore, but Jennifer is able to split them up and kills Andy with his own ax.

She then stops the boat just a few feet away from Stanley, who swims to her and attempts to lift himself out of the water via the motor. He begs her not to kill him, insisting that he’s sorry and that it was never his idea in the first place. Jennifer answers his pleas by repeating his own words back to him—“Suck it, bitch,” she says just before she turns the motor back on and tears him apart with its underwater propeller.

For those reasons today’s subject is the rare example of a film whose content makes it almost impossible to recommend to others, while also being one that no serious student of the filmmaking arts can justifiably avoid—it’s a film that should be shown in every introductory film class, but never will be because of the protests its inclusion would inevitably engender.

I am, of course, talking about:

Originally released as Day of the Women in 1978, Polish sound editor Meir Zarchi’s directorial debut was inspired by a real life incident in which he and a friend discovered a badly beaten and nude woman who had been raped in a park near his home. Not only had he been horrified by the barbarity of the woman’s attackers (they had broken her jaw and only allowed her to live after she insisted that there was no way she could identify them since they had smashed her glasses and she could not see their faces), but also by the terrible bureaucratic indifference of the police officer who took her report and seemed far more concerned with getting it finished than calling the ambulance she so obviously needed. To Zarchi’s eyes the casual cruelty of the apathetic officer was little different than the animal savagery of the rapists and in the years that followed the incident he began to imagine a film in which a woman survives a terrible rape, but instead of going to the police for justice, decides to take the matter into her own hands and forces her attackers to understand how terrifying it is to be a victim of another person’s remorseless brutality. He wrote the screenplay during the 40-minute subway commutes to and from his New York office and was able to raise enough money (and defer enough payments) to make the film with a cast of unknowns and a crew largely composed of enthusiastic amateurs.

The film begins in New York, but only stays there for the briefest of scenes. Jennifer Hills (Camille Keaton), a successful young short story writer has decided to leave her apartment in the city in order to enjoy the peace and tranquility of a lake house located in rural Connecticut, where she plans to write her first novel. On her way there she stops for gas at the town’s antiquated station, where the attendant, Johnny (Eron Tabor) takes notice of her sophisticated beauty, while his two dimwitted friends, Andy (Gunter Kleeman) and Stanley (Anthony Nichols) play a game that involves throwing a switchblade into the grass at their feet.

Upon reaching the lake house, Jennifer is so excited by the quiet, natural beauty of her surroundings that she runs towards the water and takes off her dress and enjoys a naked swim in the water—visibly thrilled to have escaped the noise and squalor of the city.

We next see her as she unpacks her clothes and discovers a gun left behind by a former tenant in one of the drawers, but before she can do anything more than look at it, she is interrupted by the sound of someone knocking on her door. It turns out to be Matthew (Richard Pace), the Lenny-esque manchild who works as the delivery boy for the local grocery store. When he learns that she’s from New York City, he tells her that she “…comes from an evil place!” She humours his small-town innocence by giving him “…a tip from an evil New Yorker,” which he excitedly tells her is the largest he’s ever received (a whole dollar). He’s also becomes excited when he learns she’s a real writer and is famous (even though he’s never actually heard of her) and—as he chomps on an apple she gives him—he asks her if she has a boyfriend.

“I have many boyfriends,” she tells him.

“Could I be your friend?” he asks her sweetly.

“Sure,” she smiles at him.

Thrilled by his encounter with the glamorous woman from the big city, Matthew leaves and finds his friends—the same three men Jennifer encountered at the gas station. Trying to impress them he tells them that he “…saw her tits!” (referring to the fact that she wasn’t wearing a bra underneath her shirt). It’s obvious that they aren’t a good influence on him, but they’re also the only people around who treat him like an equal—largely because they’re not that much smarter than he is. Having exhausted all of the other diversionary activities their small town offers, the four of them decide to go fishing. There they discuss whether or not beautiful women have to defecate (they decide that they do, since all woman “…are full of shit”) and how they have to get Matthew “…a broad…” to rid him of his virginity. Stanley takes a shot at Matthew’s sexuality by claiming that, “…broads don’t turn him on!” to which Matthew responds by insisting, “Yes they do, but not all broads, only the special ones.” Johnny humours him by asking, “What’s a special broad, Matthew?”

“Miss Hill,” answers Matthew. “Miss Hill is special.”

Unaware of the impact she is having amongst the locals, Jennifer continues to commune with nature by going on canoe rides and sitting outside as she writes out chapters of her novel in long hand on a yellow legal pad. Her peace does not last, however, when Andy and Stanley drive by on their motorboat. Intent on getting her attention, they obnoxiously loop around the water until finally she has no choice but to go inside in order to escape them.

Later that night, while she is alone in bed, she is disturbed by the sound of clearly manmade animal noises coming from outside the house. She goes outside to see where they are coming from, but sees only the darkness of the night and decides to go back inside, where she reassures herself with the knowledge that she has the gun she found in the drawer, if she needs it. It turns out that she soon will, but at a time and place where no one would think to bring it.

During the middle of a hot summer day, Jennifer basks in the rays of the sun as she lies out in her canoe as it floats across the water. Her calm does not last long, though, as Stanley and Andy return in their motorboat. This time, however, they intend on doing more than simply show off. They begin by driving around her canoe, causing it to shake in the waves, and then they grab its rope and begin pulling it behind them. They take it to the shore, where Jennifer tries to fight them off with her paddle, but they quickly get it away from her and begin chasing her through the woods.

Jennifer soon discovers that this attack was planned when she reaches a clearing and is knocked down by Johnny, who has been waiting for his two friends to deliver her to him. With Andy and Stanley’s help he tears off her bikini, holds her down and urges Matthew to come out from his hiding spot and take what they had gotten for him. Matthew, torn between his loyalty to his friends and his affection for Miss Hill, refuses to rape her, but agrees to hold one of her legs as Johnny decides to do what he won’t. Johnny strips out of his clothes and roughly penetrates Jennifer.

When he finishes, his three friends let her go and they all watch as she crawls away into the woods. Johnny sends Matthew out to get her back, but he just helps her up and watches as she limps away. The others taunt him for not taking advantage of the situation, with Johnny telling him, “…You’re gonna die a virgin.”

Naked and barefoot, Jennifer is forced to walk through not only the forest, but also small streams and swamp water in order to get back home. Sadly, though, her attackers know the area far better than she does and are able to find her again. This time Stanley rapes her—sodomizing her as Andy and Matthew hold her down on a large rock. He climaxes as quickly as Johnny did and the four of them leave her stretched out on the rock and return to their boat. Making their escape they abandon her canoe in the middle of the lake and Johnny throws her bikini into the water.

Bruised, bloodied and covered in mud, a nearly catatonic Jennifer is finally able to get back to the lake house. Upon reaching it, she collapses and has to crawl in order to get to a shirt to cover her naked body and to then get to the phone to call the police.

But her attackers are not done with her. Just as she finishes dialing, the phone is kicked away from her and Johnny appears at the top of her stairway. As the others cheer him on, a now-drunk Matthew overcomes his shyness and strips naked and jumps on top of their victim, but isn’t able to finish like the others. As he dejectedly puts his clothes back on, Andy finds some pages from Jennifer’s unfinished novel and reads them aloud for everyone’s amusement before he tears them up and throws the ripped up pieces on top of her.

The other three having had their turns, Stanley is the last of the four to take advantage of their captive. Jennifer—knowing that she can’t stop him and has been badly hurt by the other’s rough penetrations—begs him to allow her to fellate him instead. “Total submission, that’s what I like in a woman,” he sneers just before he sadistically shoves a bottle into her vagina and orders her to perform oral sex with the command “Suck it, bitch!” Unhappy with her lack of effort, he gets up and starts kicking her, which—despite their previous barbarity—is too much for even his friends to take. They pull him outside and start to leave, but then Johnny decides that they can’t leave her alive after what they did to her. He hands Matthew a switchblade and tells him to go back inside and kill her. Matthew naturally refuses at first, but Johnny is finally able to convince him to do it. With the knife in his hand he returns inside the house, where Jennifer is laying unconscious on the floor. He puts the blade to her chest, but he can’t go through with it, so he instead wipes it across her cheek, covering it in blood, which he shows to his friends in order to prove that he did it. Assuming that they now have nothing to worry about, the four of them escape away from the house down the water in their motorboat.

Knowing that there is nothing the law can do to get her the justice she deserves for what the four men have done to her, Jennifer does not call the police. Instead she slowly nurses herself back to health and picks up the pieces of her now-shattered life. One day she spots her canoe floating in the water outside of her house and is able to retrieve it. The next she spends patiently taping up the pages from her novel that Stanley tore up in front of her and soon she starts writing new pages to go along with them. The days pass by and her visible wounds fade, leaving only the ones left on the inside—the ones she’ll have to eventually leave the lake house to cure.

As their victim convalesces, the four rapists grow concerned that she might still be alive since they had not heard any news about her body being discovered by the police. Johnny attempts to convince Matthew to go to the house to check, but he refuses and it’s left up to Andy and Stanley to find out for sure. They drive past the house on their motorboat and see their victim sitting at a tree reading a book. Knowing now that Matthew lied to them, the three others beat him up and make it clear that their friendship is over.

As the quartet self-destructs, Jennifer is finally ready to open the drawer that holds the gun she found her first day there. Dressed in black, she drives to the local church and asks God to forgive her for what she is about to do. She then drives to the gas station where Johnny works, but stops herself from carrying out her plan when she sees him with his wife and children. She then spots Matthew as he rides past her on his bicycle and decides to begin with him.

She returns home and places an order to the grocery store where he works. Upon being told of the address of his next delivery, Matthew gets scared and steals a knife from the meat counter to protect himself. When he arrives at the lake house, he finds Jennifer waiting for him outside, dressed in a white robe that makes her look like an angel. He follows her into the woods, holding up the knife he brought with him—ready to use it if he has to.

With the knife in his hand, he finds her standing beside a tree next to the water.

“I hate you! I hate you!” he cries at her angrily.

“What have I done to you Matthew?” she asks with an eerie calmness that almost borders on kindness.

“I have no friends now because of you!” he tells her.

“Why, Matthew?” she asks as she begins to untie her robe. “Why because of me?”

“Because I was chosen to kill you and I didn’t!”

“You will this time Matthew,” she says encouragingly. “You will. Just relax.”

“I’m sorry I have to do this,” he apologizes. “I’m also sorry for what I did to you with them. It wasn’t my idea. I have no friends in town.”

“I thought we were friends. Remember? You asked me.”

“You’re only here for the summer! What am I to do the rest of the year?”

“I could have given you a summer to remember—for the rest of your life,” she tells him as she pulls apart the robe and exposes one of her breasts.

With the knife still raised above his head, she shows him the rest of her naked body and pulls him in for a kiss. She then kneels down and takes off his pants and pulls him on top of her. As he has sex with her (doing now what he earlier could not), she reaches behind to a noose hidden in the leaves of the tree and slips it around his neck. She then starts pulling on the rope the noose is attached to and lifts Matthew up into the air, his body jerking spastically as he slowly suffocates. She waits until she is sure that he is dead before dumping his body and bicycle into the river. She then returns to the house and calls the grocery store to inform them that her delivery never arrived.

Having taken care of Matthew, she decides it’s time to return to Johnny. She finds him by himself at the gas station and is able to wordlessly convince him to get into her car—using nothing more a flirtatious look and a nod of her head. She drives him to a clearing, where she pulls out her gun on him and orders him to strip. Johnny does as he’s told, but rather than beg for his life he explains how what happened was really all her fault—insisting that she provoked them with her sexy clothes. Jennifer allows him to believe that she is swayed by his reasoning and hands her gun over to him and invites him back to her house. He agrees—not realizing that she is only doing so in order to make him suffer much, much more than he would have if she had just shot him.

Back at her house, she joins Johnny in her bathtub for a bubble bath as he complains about his wife and friends. He tells her that Matthew is missing, but that he’ll probably turn up sooner or later.

“He’ll never come back,” Jennifer tells him as she massages and caresses his chest.

“Why, do you think he committed suicide or something?” asks Johnny.

“No,” she answers matter-of-factly. “I killed him.”

Despite her protestations to the contrary, Johnny refuses to accept that she isn’t joking and doesn’t see it coming when Jennifer reaches for a knife she has hidden underneath a towel and uses it to castrate him. Her rapist is so relaxed in the water he doesn’t even realize it has happened until he sees the water turn red. Jennifer calmly gets out of the tub, puts on her robe and locks Johnny inside the bathroom as his cursing turns to begging for help and mercy. She drowns out his cries by playing an aria from Puccini's Manon Lescaut.

This just leaves Andy and Stanley, who—knowing that both Matthew and Johnny are missing—suspect that their own lives are in danger. Stanley approaches the house on his boat, while Andy comes by land—armed with an ax. Jennifer, swinging in her hammock in a green bikini, hears Stanley coming and surprises him by swimming to his boat and climbing in.

“Where’s your friend?” she asks him.

“He stayed back in town,” he lies to her.

“I’m glad,” she lies right back to him. “It’s you I wanted.”

As clueless as Matthew and Johnny, Stanley leans in for the implied kiss, which gives Jennifer the opportunity she needs to push him out of the boat. As he splashes in the water, she starts the motor and starts terrorizing him with the boat just like he and Andy did to her before. Andy reveals himself from where he was hiding on the shore and screams at her to leave his friend alone as he climbs into the water. Using the boat, she manages to steal away his ax and watches as Andy swims towards Stanley in a foolish attempt to rescue him. The two of them attempt to make it to shore, but Jennifer is able to split them up and kills Andy with his own ax.

She then stops the boat just a few feet away from Stanley, who swims to her and attempts to lift himself out of the water via the motor. He begs her not to kill him, insisting that he’s sorry and that it was never his idea in the first place. Jennifer answers his pleas by repeating his own words back to him—“Suck it, bitch,” she says just before she turns the motor back on and tears him apart with its underwater propeller.

As his body begins to sink into the water, Jennifer drives away. For the briefest of possible seconds a smile begins to appear on her face, but she does not allow it to grow and replaces it with a cold, blank stare.

The credits begin to roll.

I’m sure it’s pretty obvious by now where I stand in the whole misunderstood masterpiece/worst movie ever debate that has helped keep Day of the Woman relevant to this very day, but I should admit right now that I have a more personal reason to side with its creator than natural contrariness. Like Meir Zachri, I know what it’s like to make a sincere effort to create a work that both honors the strength and fortitude of women and criticizes the clueless brutality of men, only to be accused of misogyny for having created it. It actually happened to me twice, both cases involving poems I had written for two creative writing classes I had taken during my brief tenure at the University of Alberta.

The first time involved a poem I had written from the point of view of a rapist who rants at his victim for not giving him the experienced he wanted. Clearly a weak and pathetic figure who committed his crime in a sick attempt to control someone else, his effort fails when his victim refuses to break down into tears and simply stares back at him with hateful contempt. Despite having been written with the rapist’s voice, it was obvious whose side I was on and that I had intended for the creep to damn himself with his words, rather than present them as an actual defense of what he did.

It proved to be the most controversial poem the class discussed that year (literally, as nearly a 1/4 of that week’s 3 hour class ended up being devoted to it) and it was simultaneously praised by some as my best work to date and trashed by others as a work of terrible misogyny that illustrated a viewpoint that had no right to exist in the printed word. And lest you think that I’m being a bit overdramatic describing the sentiments of my detractors, I will never forget that at the end of the debate the poem inspired, our professor summed up his feelings by saying “I think this proves that some point of views should not be expressed.”

To this day it saddens and shocks me that someone who had devoted their entire life to being a writer and a poet would actually say those words out loud.

The most vocal of my detractors was the class’ most fiercely dogmatic feminist, who ignored the poem’s obvious theme of how even when victimized, women are inevitably stronger than men, and instead insisted that by giving a voice to a rapist, I became one. Never mind that the poem was a work of fiction and no crime actually occurred, as far as she was concerned my having written about a rape from the male perspective made me a (literary) rapist.

You would think that after being accused of such an offense, I would cease from that point on to write about the subject and protect myself from being labeled a disgusting misogynist for the rest of my academic life, but I was just 19 and not ready to be so easily cowed into dogmatic submission.

You would think that after being accused of such an offense, I would cease from that point on to write about the subject and protect myself from being labeled a disgusting misogynist for the rest of my academic life, but I was just 19 and not ready to be so easily cowed into dogmatic submission.

The next year nearly all of the same students were enrolled in the higher-level class with a different professor and—without even thinking about what had happened the year before—the first poem I submitted was a long and angry screed that took issue with the way woman had been treated by religion (in this case Christianity) over the years. It told the tale of Christ returning just before The Rapture specifically to rape an underage stripper on Christmas Eve (not a subtle concept to be sure, but I was only 19 when I wrote it). My professor, when he introduced it, described it as, “The most explicitly feminist poem I’ve ever read,” which—considering the kind of work he must have been exposed to over the years—struck me as a being a very bold statement, but the same woman who had accused me of being a symbolic rapist a year earlier strongly disagreed.

In this case her outrage came from the fact that I had depicted the rape in the body of the poem and—even though my narrator this time was unambiguously sympathetic to the victim and hostile to her attacker—this again was an act of misogyny on my part. As she argued her case it become quite obvious that—as far as she was concerned—rape, as a subject, was entirely off limits to any writer with a penis. The violation of undesired penetration being a subject she believed male writers could never appreciate or even remotely understand. Naturally this argument can be undone with a single viewing of any one episode of Oz or Deliverance, but I have discovered throughout the years that pointing this out seldom, if ever, inspires those who make it to reconsider their position.

In defense of my accuser, she did eventually praise me for a later poem I wrote about women who are afraid to express themselves out loud that was inspired by our talented, but very shy fellow classmate, whom every male in the class had a serious crush on, which she included in a ‘zine she put together with her roommate.

And while this explains my natural impulse to defend Zarchi’s film against accusations of the big, nasty m-word, I would gladly stifle it if I for one second believed that he actually hated women and had created the film to titillate his fellow misogynists, but having repeatedly watched the film and listened to his thoughts on the DVD commentary track I can say with 100% certainty that his intentions were pure—unfortunately the marketing plan of the film’s distributor was not.

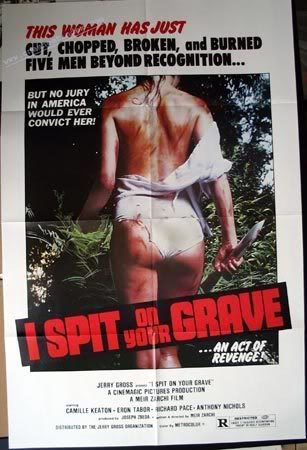

In 1978 Zarchi had successfully sold Day of the Woman across the world, but had been unable to find a distributor willing to take on the film in North America. After a very brief and unsuccessful attempt to distribute it himself, it appeared as though his film was destined to be lost to obscurity, until two years later when exploitation film distributor Jerry Gross (Blood Beach, Miss Nude America and The Boogeyman among others) agreed to release it. Against Zarchi’s wishes Gross changed the title to I Spit On Your Grave and marketed the film with a lurid poster featuring a bruised and bloodied woman’s shapely backside and the (admittedly wonderful) tagline:

The first time involved a poem I had written from the point of view of a rapist who rants at his victim for not giving him the experienced he wanted. Clearly a weak and pathetic figure who committed his crime in a sick attempt to control someone else, his effort fails when his victim refuses to break down into tears and simply stares back at him with hateful contempt. Despite having been written with the rapist’s voice, it was obvious whose side I was on and that I had intended for the creep to damn himself with his words, rather than present them as an actual defense of what he did.

It proved to be the most controversial poem the class discussed that year (literally, as nearly a 1/4 of that week’s 3 hour class ended up being devoted to it) and it was simultaneously praised by some as my best work to date and trashed by others as a work of terrible misogyny that illustrated a viewpoint that had no right to exist in the printed word. And lest you think that I’m being a bit overdramatic describing the sentiments of my detractors, I will never forget that at the end of the debate the poem inspired, our professor summed up his feelings by saying “I think this proves that some point of views should not be expressed.”

To this day it saddens and shocks me that someone who had devoted their entire life to being a writer and a poet would actually say those words out loud.

The most vocal of my detractors was the class’ most fiercely dogmatic feminist, who ignored the poem’s obvious theme of how even when victimized, women are inevitably stronger than men, and instead insisted that by giving a voice to a rapist, I became one. Never mind that the poem was a work of fiction and no crime actually occurred, as far as she was concerned my having written about a rape from the male perspective made me a (literary) rapist.

You would think that after being accused of such an offense, I would cease from that point on to write about the subject and protect myself from being labeled a disgusting misogynist for the rest of my academic life, but I was just 19 and not ready to be so easily cowed into dogmatic submission.

You would think that after being accused of such an offense, I would cease from that point on to write about the subject and protect myself from being labeled a disgusting misogynist for the rest of my academic life, but I was just 19 and not ready to be so easily cowed into dogmatic submission.The next year nearly all of the same students were enrolled in the higher-level class with a different professor and—without even thinking about what had happened the year before—the first poem I submitted was a long and angry screed that took issue with the way woman had been treated by religion (in this case Christianity) over the years. It told the tale of Christ returning just before The Rapture specifically to rape an underage stripper on Christmas Eve (not a subtle concept to be sure, but I was only 19 when I wrote it). My professor, when he introduced it, described it as, “The most explicitly feminist poem I’ve ever read,” which—considering the kind of work he must have been exposed to over the years—struck me as a being a very bold statement, but the same woman who had accused me of being a symbolic rapist a year earlier strongly disagreed.

In this case her outrage came from the fact that I had depicted the rape in the body of the poem and—even though my narrator this time was unambiguously sympathetic to the victim and hostile to her attacker—this again was an act of misogyny on my part. As she argued her case it become quite obvious that—as far as she was concerned—rape, as a subject, was entirely off limits to any writer with a penis. The violation of undesired penetration being a subject she believed male writers could never appreciate or even remotely understand. Naturally this argument can be undone with a single viewing of any one episode of Oz or Deliverance, but I have discovered throughout the years that pointing this out seldom, if ever, inspires those who make it to reconsider their position.

In defense of my accuser, she did eventually praise me for a later poem I wrote about women who are afraid to express themselves out loud that was inspired by our talented, but very shy fellow classmate, whom every male in the class had a serious crush on, which she included in a ‘zine she put together with her roommate.

And while this explains my natural impulse to defend Zarchi’s film against accusations of the big, nasty m-word, I would gladly stifle it if I for one second believed that he actually hated women and had created the film to titillate his fellow misogynists, but having repeatedly watched the film and listened to his thoughts on the DVD commentary track I can say with 100% certainty that his intentions were pure—unfortunately the marketing plan of the film’s distributor was not.

In 1978 Zarchi had successfully sold Day of the Woman across the world, but had been unable to find a distributor willing to take on the film in North America. After a very brief and unsuccessful attempt to distribute it himself, it appeared as though his film was destined to be lost to obscurity, until two years later when exploitation film distributor Jerry Gross (Blood Beach, Miss Nude America and The Boogeyman among others) agreed to release it. Against Zarchi’s wishes Gross changed the title to I Spit On Your Grave and marketed the film with a lurid poster featuring a bruised and bloodied woman’s shapely backside and the (admittedly wonderful) tagline:

This woman has just cut, chopped, broken and burned five men beyond recognition...

But no jury in America would ever convict her!

Despite the tagline’s three major inaccuracies (Jennifer only kills four men, doesn’t burn any of them and would most likely still get convicted in Texas), it did the trick and got the film in theaters around the country, including—most significantly—Chicago where a single review branded the film with its infamous reputation and sparked the debate that surrounds it to this day.

Since he saw it in 1980, Roger Ebert has never hesitated in naming I Spit On Your Grave as the worst film he has ever reviewed. Such was his antipathy for the film, he actually appointed himself the role of public censor and urged people to boycott and protest the theaters that were showing it and on several occasions stood outside those theaters with his fellow famous TV reviewing partner Gene Siskel in order to try and convince people not to see it. For the moment, he proved successful, as the film quickly disappeared out of theaters, but in the long run his efforts were undone when—thanks largely to its now-infamous reputation—the film became a huge hit following its release into the then-nascent home video market.

The irony being one that every potential crusader should note—in all likelihood your protests will give the subject of your ire more attention than it ever would have received if you had simply allowed it to come and go without comment.

And while Ebert certainly was well within his rights to loathe the film and do everything he could to spare others what he believed was the most horrible of cinematic experiences, his reaction to the film was troubling for several reasons, the first of which was utter hypocrisy.

In the decade preceding his review of I Spit on Your Grave, Ebert had occasionally moonlighted as a screenwriter for the infamously breast-obsessed director Russ Meyer (both pictured) and collaborated on the scripts that would eventually become Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, Up! and Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens. And while the three films vary greatly in quality (Beyond is brilliant, Up! is extremely uneven but has its moments and Beneath is a self-indulgent mess) each of them contains moments as discomfiting as any found in Zarchi’s film. In particular, the deaths of Casey and Roxanne in Beyond (who essentially die for no other reason than their lesbian relationship), the extended and brutal rape of Margo in Up! and the numerous sexual assaults played for laughs in Beneath, all call into question the validity of Ebert’s moral crusade against the film.

Equally distressing is the fact that eight years earlier Ebert (to his credit) had been one of the few critics to defend Wes Craven’s disturbing breakout film, The Last House on the Left--a film one could easily argue is as “…sick, reprehensible and contemptible…” as I Spit on Your Grave, if not more so. But it is clear when you read his review of I Spit on Your Grave, what has offended him is not so much the film’s content, but rather how the audience he watched it with reacted to it.

Reading his description of the vocal reactions of his fellow audience members cheering on the rapists as they assaulted their victim, it is easy to understand why he left the screening feeling so disturbed, but it is much harder to sympathize with his conclusion that this was the precisely the reaction the filmmakers had intended.

I remember when Schindler’s List came out there were reports of laughter from callous teenagers on school field trips, who reacted to the senseless deaths of Jewish holocaust victims the exact same way they would later react to the senseless deaths of the underworld characters in Pulp Fiction. Had Ebert seen Spielberg’s movie in a theater filled with these idiots, would he have concluded that the director was an amoral anti-semite playing the Shoah for laughs? Of course not, but Spielberg’s film had the benefit of being marketed as the serious work that it was—while Zarchi’s film had had its title changed and was now being sold as a pure exploitation picture. The question then is if Ebert’s review would have stayed the same if he had seen Day of the Woman instead of I Spit on Your Grave. My guess is that under its original title, the film wouldn’t have attracted the rough, unenlightened crowd that responded so enthusiastically to the ads for I Spit on Your Grave and Ebert would have simply dismissed the film rather than be inspired to declare the jihad that helped make it so famous.

In retrospect the most troubling part of Ebert’s review is his insistence that, “This is a film without a shred of artistic distinction. It lacks even simple craftsmanship,” since watching the film today clearly proves this not to be the case, but in the critic’s defense it is certainly likely that the film he saw and heard at a local theater in 1980 bears little resemblance to the film now available on DVD in 2007. In the past few years we have seen a rise in once-dismissed or even actively abhorred films receive the benefit of a critical re-evaluation thanks largely to remastered DVD releases that present them in a new and entirely different light. It is entirely possible that the film Ebert saw appeared to be poorly made, but the film available right now proves that initial appearances can be deceiving.

There is a reason I took the time and effort to format this post so that its screencaps could be enlarged with a mouse click and that is because many of them possess a deceptively simple beauty that I felt was ill served by presenting them at only 350x190 resolution. The film possesses a unique look that at once seems dreamlike and verite-esque (is so a word)—as if Zarchi has made a fly-on-the-wall 70s documentary of a horrible nightmare. Zarchi and his cinematographer Yuri Haviv (who also shot the genuinely artless Doris Wishman curiosity Double Agent 73) take full advantage of the natural settings of Kent, Connecticut, to create an arresting juxtaposition of savage inhumanity and lush green floral beauty.

But even if this were not the case, I believe Ebert is completely mistaken when he argues that, “Because [the film] is made artlessly, it flaunts its motives: There is no reason to see this movie except to be entertained by the sight of sadism and suffering.” In fact, I would argue that the exact opposite is true—it is the perceived lack of artistry that actually proves that Zarchi’s motives were to invoke horror and empathy for his victim and not to titillate the sadists whose laughter and jokes caused Ebert to so passionately lash out.

The attack on Jennifer (starting from Andy and Stanley abducting her canoe and ending with the four rapists escaping from the lake house via their motor boat) lasts just a bit over 32 minutes, which is almost less than half as long as the “…hour of rape scenes…” Ebert describes, but still long enough to make it one of the most significantly extended rape sequences in film history. For many it is this extended length that the film’s detractors point to as the clearest sign of Day of the Woman’s perceived misogyny—arguing that the film could have simply suggested the attack if it intentions were to enlighten rather than to arouse—but in reality the opposite is once again true.

Equally distressing is the fact that eight years earlier Ebert (to his credit) had been one of the few critics to defend Wes Craven’s disturbing breakout film, The Last House on the Left--a film one could easily argue is as “…sick, reprehensible and contemptible…” as I Spit on Your Grave, if not more so. But it is clear when you read his review of I Spit on Your Grave, what has offended him is not so much the film’s content, but rather how the audience he watched it with reacted to it.

Reading his description of the vocal reactions of his fellow audience members cheering on the rapists as they assaulted their victim, it is easy to understand why he left the screening feeling so disturbed, but it is much harder to sympathize with his conclusion that this was the precisely the reaction the filmmakers had intended.

I remember when Schindler’s List came out there were reports of laughter from callous teenagers on school field trips, who reacted to the senseless deaths of Jewish holocaust victims the exact same way they would later react to the senseless deaths of the underworld characters in Pulp Fiction. Had Ebert seen Spielberg’s movie in a theater filled with these idiots, would he have concluded that the director was an amoral anti-semite playing the Shoah for laughs? Of course not, but Spielberg’s film had the benefit of being marketed as the serious work that it was—while Zarchi’s film had had its title changed and was now being sold as a pure exploitation picture. The question then is if Ebert’s review would have stayed the same if he had seen Day of the Woman instead of I Spit on Your Grave. My guess is that under its original title, the film wouldn’t have attracted the rough, unenlightened crowd that responded so enthusiastically to the ads for I Spit on Your Grave and Ebert would have simply dismissed the film rather than be inspired to declare the jihad that helped make it so famous.

In retrospect the most troubling part of Ebert’s review is his insistence that, “This is a film without a shred of artistic distinction. It lacks even simple craftsmanship,” since watching the film today clearly proves this not to be the case, but in the critic’s defense it is certainly likely that the film he saw and heard at a local theater in 1980 bears little resemblance to the film now available on DVD in 2007. In the past few years we have seen a rise in once-dismissed or even actively abhorred films receive the benefit of a critical re-evaluation thanks largely to remastered DVD releases that present them in a new and entirely different light. It is entirely possible that the film Ebert saw appeared to be poorly made, but the film available right now proves that initial appearances can be deceiving.

There is a reason I took the time and effort to format this post so that its screencaps could be enlarged with a mouse click and that is because many of them possess a deceptively simple beauty that I felt was ill served by presenting them at only 350x190 resolution. The film possesses a unique look that at once seems dreamlike and verite-esque (is so a word)—as if Zarchi has made a fly-on-the-wall 70s documentary of a horrible nightmare. Zarchi and his cinematographer Yuri Haviv (who also shot the genuinely artless Doris Wishman curiosity Double Agent 73) take full advantage of the natural settings of Kent, Connecticut, to create an arresting juxtaposition of savage inhumanity and lush green floral beauty.

But even if this were not the case, I believe Ebert is completely mistaken when he argues that, “Because [the film] is made artlessly, it flaunts its motives: There is no reason to see this movie except to be entertained by the sight of sadism and suffering.” In fact, I would argue that the exact opposite is true—it is the perceived lack of artistry that actually proves that Zarchi’s motives were to invoke horror and empathy for his victim and not to titillate the sadists whose laughter and jokes caused Ebert to so passionately lash out.

The attack on Jennifer (starting from Andy and Stanley abducting her canoe and ending with the four rapists escaping from the lake house via their motor boat) lasts just a bit over 32 minutes, which is almost less than half as long as the “…hour of rape scenes…” Ebert describes, but still long enough to make it one of the most significantly extended rape sequences in film history. For many it is this extended length that the film’s detractors point to as the clearest sign of Day of the Woman’s perceived misogyny—arguing that the film could have simply suggested the attack if it intentions were to enlighten rather than to arouse—but in reality the opposite is once again true.

Strangely, those offended by the sequence’s “artlessness” and extended length complain that it is ugly, unbearably sadistic and nearly impossible for a decent person to sit through, which is an extremely odd criticism when you consider that they are talking about—and please forgive me as I use a profanity to express myself—A FUCKING RAPE SCENE! By its very definition rape is an ugly, sadistic crime that no decent person would be comfortably able to watch happen in front of them. The rape scenes in Day of the Woman are disgusting because they were meant to be disgusting. Zarchi’s intentions are clear, he wants you to feel sick as you watch what happens to Jennifer and if you don’t than that is a damning failure of your own soul, not his as a filmmaker.

Beyond its length, there are several other factors that make the sequence unique amongst its ilk. The first is the unusual use of male nudity. In most films involving rape, it is almost always only the victim who is seen naked, but in Day of the Woman, all but one of Jennifer’s four attackers strip down to nothing but their socks. There is a reason male nudity is still extremely rare in movies, especially when compared to its female counterpart, and that’s because many people—both male and female—are repulsed by it. In the majority of cinematic rape scenes, the filmmakers only show us genitalia we are hardwired to find arousing, thus making their sequences more potentially titillating than they would want to admit. Zarchi avoids this trap by showing just as much of Johnny, Andy and Matthew’s bodies as he does as Jennifer’s. This contributes significantly to the sense of disgust decent audiences feel when they watch the film.

But the aspect of the sequence that most significantly makes it stand out is its use of music—there is none. With the exception of the scene where Jennifer puts on an opera record to drown out Johnny’s cries for help, there is no music in Day of the Woman. More than anything else, this lack of a traditional score contributes to the film’s documentary-like feel—the absence of the expected emotional cues tricks us into thinking that what we are seeing is really happening and not a work of imagination. This more than anything else is why I believe Ebert became convinced that Zarchi’s film was an “…expression of the most diseased and perverted darker human natures.” Without a musical score to tell him what Zarchi wanted him to feel at that moment, it was easy for him to conclude that the filmmaker was in league with the sick fucks he was unfortunate enough to be sitting with in the theater.

To my eyes, Zarchi did everything he could to make the sequence as hard to watch as possible, with the sole exception of casting an unattractive woman as the victim (but even his decision to cast the beautiful Keaton--pictured here from a horror convention appearance she made at the age of 55--in the role is one that makes sense on both a thematic and narrative level). And while I believe he did this out of a genuine desire to document the true horrors of sexual assault, the sequence’s brutality also serves the vital purpose of justifying Jennifer’s own remorseless brutality in the last half of the film.

To my eyes, Zarchi did everything he could to make the sequence as hard to watch as possible, with the sole exception of casting an unattractive woman as the victim (but even his decision to cast the beautiful Keaton--pictured here from a horror convention appearance she made at the age of 55--in the role is one that makes sense on both a thematic and narrative level). And while I believe he did this out of a genuine desire to document the true horrors of sexual assault, the sequence’s brutality also serves the vital purpose of justifying Jennifer’s own remorseless brutality in the last half of the film.

In her brilliant defense of the film in her landmark book Men, Women and Chainsaws (perhaps the most often cited text in the history of this blog), Carol J. Clover points out that Roger Ebert never mentions how the twisted souls who laughed at Jennifer’s suffering reacted when she turned against her attackers in the most violent ways possible. Did they laugh when she cut off Johnny’s penis or hung the pathetic Matthew? They might have, but my guess is that they didn’t.

More than anything else, the reason my gut reaction to Day of the Woman is to call it a work of overt feminist propaganda is the fact that the only sequences where I feel Zarchi does take some sadistic delight are the ones where Jennifer kills hers attackers. Unlike the rape sequence, which he made as ugly as possible, the three sequences where she gets her revenge are far more aesthetically pleasing and—at times—oddly and disturbingly beautiful.

The major criticism of these sequences has always been that Jennifer uses her sexuality in order to commit her murders, suggesting that as a woman she has no other weapons in her arsenal. My argument against this is that Jennifer is presented as being a smart, worldly young woman and she is canny enough to realize that seducing her victims before killing them allows her to get closer to them and make them suffer that much more than if she merely attacked them from a distance. And in the case of Matthew, her seduction not only allows her to disarm him and put him in a position where she can slip her waiting noose around his neck, but also justify her unwillingness to spare him despite his unfortunate condition and personal predicament. By allowing him to do to her what he originally couldn’t, she turns him into a man, which makes him no longer an object of pity, but rather one of deserved scorn.

Beyond its length, there are several other factors that make the sequence unique amongst its ilk. The first is the unusual use of male nudity. In most films involving rape, it is almost always only the victim who is seen naked, but in Day of the Woman, all but one of Jennifer’s four attackers strip down to nothing but their socks. There is a reason male nudity is still extremely rare in movies, especially when compared to its female counterpart, and that’s because many people—both male and female—are repulsed by it. In the majority of cinematic rape scenes, the filmmakers only show us genitalia we are hardwired to find arousing, thus making their sequences more potentially titillating than they would want to admit. Zarchi avoids this trap by showing just as much of Johnny, Andy and Matthew’s bodies as he does as Jennifer’s. This contributes significantly to the sense of disgust decent audiences feel when they watch the film.

But the aspect of the sequence that most significantly makes it stand out is its use of music—there is none. With the exception of the scene where Jennifer puts on an opera record to drown out Johnny’s cries for help, there is no music in Day of the Woman. More than anything else, this lack of a traditional score contributes to the film’s documentary-like feel—the absence of the expected emotional cues tricks us into thinking that what we are seeing is really happening and not a work of imagination. This more than anything else is why I believe Ebert became convinced that Zarchi’s film was an “…expression of the most diseased and perverted darker human natures.” Without a musical score to tell him what Zarchi wanted him to feel at that moment, it was easy for him to conclude that the filmmaker was in league with the sick fucks he was unfortunate enough to be sitting with in the theater.

To my eyes, Zarchi did everything he could to make the sequence as hard to watch as possible, with the sole exception of casting an unattractive woman as the victim (but even his decision to cast the beautiful Keaton--pictured here from a horror convention appearance she made at the age of 55--in the role is one that makes sense on both a thematic and narrative level). And while I believe he did this out of a genuine desire to document the true horrors of sexual assault, the sequence’s brutality also serves the vital purpose of justifying Jennifer’s own remorseless brutality in the last half of the film.

To my eyes, Zarchi did everything he could to make the sequence as hard to watch as possible, with the sole exception of casting an unattractive woman as the victim (but even his decision to cast the beautiful Keaton--pictured here from a horror convention appearance she made at the age of 55--in the role is one that makes sense on both a thematic and narrative level). And while I believe he did this out of a genuine desire to document the true horrors of sexual assault, the sequence’s brutality also serves the vital purpose of justifying Jennifer’s own remorseless brutality in the last half of the film.In her brilliant defense of the film in her landmark book Men, Women and Chainsaws (perhaps the most often cited text in the history of this blog), Carol J. Clover points out that Roger Ebert never mentions how the twisted souls who laughed at Jennifer’s suffering reacted when she turned against her attackers in the most violent ways possible. Did they laugh when she cut off Johnny’s penis or hung the pathetic Matthew? They might have, but my guess is that they didn’t.

More than anything else, the reason my gut reaction to Day of the Woman is to call it a work of overt feminist propaganda is the fact that the only sequences where I feel Zarchi does take some sadistic delight are the ones where Jennifer kills hers attackers. Unlike the rape sequence, which he made as ugly as possible, the three sequences where she gets her revenge are far more aesthetically pleasing and—at times—oddly and disturbingly beautiful.

The major criticism of these sequences has always been that Jennifer uses her sexuality in order to commit her murders, suggesting that as a woman she has no other weapons in her arsenal. My argument against this is that Jennifer is presented as being a smart, worldly young woman and she is canny enough to realize that seducing her victims before killing them allows her to get closer to them and make them suffer that much more than if she merely attacked them from a distance. And in the case of Matthew, her seduction not only allows her to disarm him and put him in a position where she can slip her waiting noose around his neck, but also justify her unwillingness to spare him despite his unfortunate condition and personal predicament. By allowing him to do to her what he originally couldn’t, she turns him into a man, which makes him no longer an object of pity, but rather one of deserved scorn.

In other words, she has to fuck him so she can kill him.

In the sequence with Johnny, Jennifer proves her status as the most powerful of the two by first wordlessly convincing him to get into her car and then pretending to be swayed by his ridiculously chauvinistic defense of his crime against her, so she can put him in position to be robbed of the one thing he cares about most. Without even really trying she is able to expertly exploit his delusional narcissism and get him into that bathtub where a very sharp knife is waiting for her beneath a nearby towel.

Interestingly, in these two sequences Zarchi uses female nudity in the exact opposite way he did male nudity during the rape sequence. Unlike the scenes featuring her assault, Zarchi wants us to enjoy watching Matthew and Johnny suffer, so he uses Camille Keaton’s body to provide the titillation he previously worked so hard to avoid. Her beauty distracts us from the ugliness of her actions, which might otherwise cause us to cease to empathize with her. Thus his apparent exploitation actually serves as an example of his feminist intent. By emphasizing her beauty in these moments he proves his allegiance to her and makes it obvious that he considers her actions just.

At this point I still have a lot more I could say about Day of the Woman (I haven’t even touched on the secondary theme of the conflict between urban and rural culture or the strange fact that in criticizing the film some feminist academic reviewers express sentiments nearly identical to that of the uber-chauvinist, Johnny) but this entry is now awfully close to being 7000 words long and I think it’s time for me to stop and get this sucker posted. That I, or anyone else for that matter, could be inspired to write at such length about this film goes a long way to negating the sentiments of those who would dismiss it as just another example of low-budget exploitation filmmaking that happened to become infamous because of one vitriolic review from a nationally-recognized film critic. In my introduction I suggested that Day of the Woman/I Spit on Your Grave was a film that is impossible to recommend, but having reached the end of this post, I feel duty bound to contradict myself—see this movie. The most-recent DVD release of the film, which not only contains the best visual and audible example of the film to date, also contains two extremely interesting audio commentary tracks by Meir Zarchi (who gave no interviews about the film for over 20 years following its release) and by genre critic and historian John Bloom (aka Joe Bob Briggs) and is one of those rare special editions that is truly special and is a must have in the collection of any serious cineaste—genre or otherwise.

In the sequence with Johnny, Jennifer proves her status as the most powerful of the two by first wordlessly convincing him to get into her car and then pretending to be swayed by his ridiculously chauvinistic defense of his crime against her, so she can put him in position to be robbed of the one thing he cares about most. Without even really trying she is able to expertly exploit his delusional narcissism and get him into that bathtub where a very sharp knife is waiting for her beneath a nearby towel.

Interestingly, in these two sequences Zarchi uses female nudity in the exact opposite way he did male nudity during the rape sequence. Unlike the scenes featuring her assault, Zarchi wants us to enjoy watching Matthew and Johnny suffer, so he uses Camille Keaton’s body to provide the titillation he previously worked so hard to avoid. Her beauty distracts us from the ugliness of her actions, which might otherwise cause us to cease to empathize with her. Thus his apparent exploitation actually serves as an example of his feminist intent. By emphasizing her beauty in these moments he proves his allegiance to her and makes it obvious that he considers her actions just.

At this point I still have a lot more I could say about Day of the Woman (I haven’t even touched on the secondary theme of the conflict between urban and rural culture or the strange fact that in criticizing the film some feminist academic reviewers express sentiments nearly identical to that of the uber-chauvinist, Johnny) but this entry is now awfully close to being 7000 words long and I think it’s time for me to stop and get this sucker posted. That I, or anyone else for that matter, could be inspired to write at such length about this film goes a long way to negating the sentiments of those who would dismiss it as just another example of low-budget exploitation filmmaking that happened to become infamous because of one vitriolic review from a nationally-recognized film critic. In my introduction I suggested that Day of the Woman/I Spit on Your Grave was a film that is impossible to recommend, but having reached the end of this post, I feel duty bound to contradict myself—see this movie. The most-recent DVD release of the film, which not only contains the best visual and audible example of the film to date, also contains two extremely interesting audio commentary tracks by Meir Zarchi (who gave no interviews about the film for over 20 years following its release) and by genre critic and historian John Bloom (aka Joe Bob Briggs) and is one of those rare special editions that is truly special and is a must have in the collection of any serious cineaste—genre or otherwise.