Once upon a time a person could reasonably expect that whenever they went to see a movie one of the last things they would ever have to watch was the sight of a man’s penis being forcibly removed from his body.

Those times are over.

In the past few years a handful of filmmakers have taken it upon themselves to break what could be consider one of the last remaining cinematic taboos and deliver unto their audiences startlingly graphic depictions of castration. Now that’s not to say they were the first to do this, as the history of exploitation cinema is peppered with titles that were willing to take aim straight at the area responsible for their male audiences’ most common and immediate fears.

For example, there’s the famous scene in

Ilsa, She-Wolf of the S.S., in which the title character (memorably played by the unforgettable

Dyanne Thorne) informs her now-former lover that it is her habit to neuter a man once he is no longer able to satisfy her insatiable sexual demands and then goes on to prove it with a very sharp surgical implement (an act that allows for the irony of her eventually being undone by his replacement, a Polish soldier whose priapism leads to her finally meeting her match). Although the scene is nowhere near as graphic as the ones about to be discussed, it is interesting insofar as it’s the one significant act of violence against a male character in a film whose central theme is literally built upon the presentation of violence against women (Ilsa’s pet theory being that women are naturally capable of absorbing more pain than men, which she attempts to prove by inflicting a series of graphic tortures against every busty soft-core actress who was working in 1975). One gets the sense that by presenting us with what most would consider the ultimate form of brutality that can be committed against a man, the filmmakers were hoping to offset the blatant misogyny of the rest of the film.

It doesn’t, but at least they made the effort.

A much, much,

much more extreme historic example of cinematic castration came courtesy of Doris Wishman, the infamous Floridian filmmaker whose oeuvre of soft-core sex flicks rank among the most ostentatiously repellent films ever made. For her 1978 “documentary” (note: the term documentary generally implies a level of professionalism Wishman was never capable of at any time during her career, thus the use of quotation marks in this instance)

Let Me Die A Woman, Wishman went so far as to film an actual sexual reassignment surgery, thus giving the world the most graphic depiction of male genital mutilation ever shown in an actual movie theater. One can only assume that there was a dramatic drop in popcorn sales wherever the movie was shown. Suffice it to say, I myself know this film only by its reputation and will happily spend the rest of my life never having seen it. And lest you think me a lightweight for this admission, I have sat through her 1974 “classic”

Double Agent 73--in which the supremely unattractive Chesty Morgan plays a spy with a special camera surgically implanted in one of her enormously floppy breasts--and in so doing suffered more than many of you can possibly imagine.

And, of course, there’s the scene

I discussed in Day of the Woman where Camille Keaton gets revenge for her vicious, extended gang-rape by cutting off the junk of the guy who made it happen, as well as several more examples I’m too lazy to mention because if I did I’d have to link to their IMDb pages and that takes more time and effort than you’d ever think it would. So, yes, there is a precedent of cinematic castration throughout the history of the art, but it’s only in the past few years that filmmakers have been so increasingly happy to take it to the furthest possible cringe-inducing level.

The most successful of these new castration films, both financially and critically, has to be Robert Rodriguez’s highly stylized adaptation of Frank Miller’s classic noir comic book,

Sin City. In that film, Bruce Willis, playing Hartigan—a cop who has spent years in jail for a crime he didn’t commit—finally gets his revenge against the deformed pedophilic senator’s son whose depraved acts sent him there. After rescuing the young stripper whose jailhouse letters kept him alive, Hartigan vents his rage against that yellow bastard by grabbing his yellow cock and pulling it right off of his yellow body. It’s a startling scene, especially since it features such an iconic performer in Willis doing the deed (and, yes, we have reached an age where Willis can justifiably be considered iconic), but this is the only time I’m going to mention it in this post because it doesn’t fit in with the previously unmentioned sub-theme I want to discuss, insofar that it involves a dude ripping off another dude’s dick, while all of the others involve much less craggy and more attractive usurpers of male penile domination.

The reality is that my interest in this recent phenomenon has less to do with any natural fascination with castration (I am, after all, a man and I happen to revere my phallus as much as any other Tom, Dick or Harry), but rather with the characters shown to be doing the castrating. One is a wealthy young woman who is driven to commit her violent act as a desperate means of survival. Another is a girl whose motives and identity are so clouded in mystery it’s possible to assume she’s not even human, but instead a divine angel of vengeance sent forth to avenge a terrible crime. And the last is a true innocent whose strange “adaptation” turns her into the living embodiment of one of the world’s oldest and most universal of myths. All three of them begin their stories as victims, but end them stronger than they were before—proving that the most extreme feminists were right, female empowerment really is just a matter of slicing off some dick's dick.

When I say that I am stunned and perplexed by the reaction Eli Roth’s

Hostel: Part II received when it was released, I am speaking just as much as the serious cineste who can spend hours talking about the films of the usual gang of European arthouse auteurs as I am the genre enthusiast who’s devoted hours of his life deconstructing the thematic intricacies of

Slumber Party Massacre II. While my low-opinion of mainstream critics allowed me to expect that they would lack the insight to look beyond its premise and controversially graphic torture set pieces, I was shocked when many genre fans equally failed to grasp how successfully it worked as a sophisticated piece of Swiftian style satire. Rather than acknowledge the interesting themes Roth chose to explore in this second film, both groups focused solely on its scenes of violence and dubbed the film a mere gender-reversed replica of the original.

But I would argue that by simply reversing the genders of his protagonists, Roth created what was both an inherently more interesting and thematically insightful film. Whereas the first film focused on the irony of foreign tourists who use their wealth to exploit people in other countries, only to themselves become much more heinously exploited by far wealthier tourists with much more depraved tastes, the second takes a broader look at the global society in which such an underground industry could actively flourish. In

Hostel it is easy to imagine that had he not been lured into the enterprise as a victim, Jay Hernandez’s character, Paxton, would eventually grow up to become one of its customers, if only because of his stereotypical alpha-male tendencies and willingness to use the misfortune of others as a means to satisfy his own carnal pleasures. The same cannot be said for Beth (Laura Germain) the second film’s protagonist, who—largely by virtue of her femininity—is infinitely more sympathetic and vulnerable than her predecessor, which makes her final transformation that much more dramatic and interesting.

For those of you who have yet to see either film, both are about a small town in Slovakia whose local economy revolves around luring young tourists into their quaint hostel, where they are subsequently kidnapped and sent to an abandoned Soviet-era concrete monstrosity. There they are sold to wealthy businessmen who travel from across the world for the opportunity to enjoy the experience of torturing and killing another person without consequence. While for most viewers the horror in both films lies in their graphic depictions of torture, I personally feel this is strongly superseded by the both the existence of the enterprise that allows this torture to happen and its apparent popularity. As far as I’m concerned the most chilling sequence of the two films occurs in

Part II, just after Beth and her two friends, Lorna and Whitney, have arrived at the titular hostel and—without their knowing it—have become the objects of desire in an international bidding war over the right to maim and kill them.

Just as Jonathan Swift satirized the heartless apathy of the ruling class by soberly suggesting that the solution to ending poverty was to eat the children of the poor, so too does Roth take aim at a culture of wealth that has become so bored with its own idle banality that the only way its members can feel something is by killing another human being. In the second film he pursues this theme far further than in the original by including a B-plot involving the two men who have won the right to kill Beth and Whitney (Lorna having been sold to a Bathory-esque older woman who enjoys bathing in the blood of virgins). Through them we are given a glimpse into the inner-workings of the business and the rules by which it is operated.

Watching the two friends interact it’s hard not to think of the two similar characters in Neil LaBute’s directorial debut

In the Company of Men who decide to avenge their frustrations towards women by deliberately humiliating the most innocent woman they can find. Todd (Richard Burgi) is the ringleader and alpha-male, while Stuart (Roger Bart) is the follower, who reluctantly goes along on the trip despite his grave moral concerns about what they are doing. In that way they also resemble the two main protagonists from the first film, Paxton and Josh (Derek Richardson). The clear subtext in the first

Hostel was that Josh allowed himself to be ordered around by his more dominant friend because their manly adventures allowed him to avoid confronting his own closeted homosexuality, while in

Part II Stuart follows Todd because their adventures together (all of which the far-wealthier Todd pays for) represent the only times in his life where he is able to escape the stifling bonds of his career and familial obligations.

But as their stories continue and the two friends at last find themselves in their leather butcher aprons and alone with the women they are now contractually obligated to murder (the organization’s secrecy is maintained by a kind of mutually assured destruction in which everyone who takes part is as guilty as everyone else) the true nature of their personalities come out. Todd, the pure hedonist, who has dressed Whitney in the costume of a low-rent prostitute, at first seems to enjoy the experience, teasing his victim with a circular saw. But when he slips and the weapon connects with her face and does actual damage, the seriousness and horror of the situation finally dawns on him. Suddenly aware that this is not a game and that he is in a room with a real human being who screams and bleeds when she is injured, he panics and runs out of the room. Informed that he must finish her off in order to meet his obligation, he refuses and is then mauled to death by a group of dogs kept around for just such occasions.

Stuart’s first instincts, on the other hand, are to attempt to rescue Beth—who he has dressed in the casual business attire worn by the women in his day-to-day life—but as the reality of the situation becomes more apparent to him he realizes he really

does want to kill her. Finally given a true outlet for all of the frustrations and humiliations he has swallowed down over the years, he realizes he actually relishes the chance to take it. Given the opportunity to finish off Whitney for a reasonable discount, he happily decapitates her with a machete before returning to Beth, who has come to represent in his mind all of the women who have embarrassed and "castrated" him throughout his life.

But Beth is a very resourceful young woman.

More than anything it is her journey that I feel elevates Hostel: Part II to a far greater level than its detractors allow. A very wealthy young woman following the death of her father, Beth has not only the will but also the resources required to be a kind and generous person. Far more sensible than her party-girl friend Whitney, but also more cautious than the naïve Lorna, Beth is the most grounded and centered character in the film (her one quirk being her very strong and visceral reaction to anyone who calls her the dreaded c-word). For this reason she is able to keep her head and figure out a way out of the torture chamber fate has thrown her into. When Stuart returns to kill her, she is able to reverse their situations and attempts to bargain her way out with the man in charge. The fate of his manhood (and life) literally in her hands, Stuart is unable to contain his rage and says the one thing guaranteed to ensure his emasculation.

Beth's transformation from pure victim to tattooed member of the exclusive Hostel club suggests that the truly unequal dynamic in Western culture isn't Male/Female, but instead Rich/Poor. Paxton's luck and resourcefulness allowed him a small modicum of revenge against his tormentors, but ultimately his relative poverty doomed him to an inevitably violent death (the second film begins with his being decapitated in the one place where he feels safe and, later on in the film, his severed head is shown as the centerpiece in the Chairman's grotesque trophy room), whereas Beth is able to ensure her continued survival thanks to her inherited wealth. For this reason there is a tremendous amount of sadness in her victory. Despite her tremendous courage and intelligence, she escapes only because Stuart lacks the financial resources of his dead friend. In the twisted logic of the world in which they live, she emasculates Stuart before she cuts off his dick simply by having a larger net worth than he does.

It is, in fact, this feeling of being less than--which he blames on his wife--that causes Stuart to forget his heroic instincts and embrace the worst impulses of his wounded masculinity. Thus fate ensures that his symbolic castration becomes a literal one at the hands of a woman who he has subconsciously dressed in the attire of his metaphorical emasculater.

If one truly wanted to criticize Roth's film, you could argue that it lacks subtlety and his conclusions are fairly obvious. I would disagree insofar as I believe that subtle satire is an oxymoron and that those filmmakers who attempt it inevitably create trite works of little to no impact. And being obvious is usually only considered a fault by those viewers whose own detachment leads them to believe that "truth" is a fantasy of the bourgeoisie (ie. most professional critics). The problem is that either through deliberate obtuseness or inadvertent obliviousness many commentators, both mainstream and genre, refuse to acknowledge that the Hostel films exist on any other level than the showcasing of graphic violence--neglecting to criticize their themes not because they disagree with them but because they cannot bring themselves to admit that they exist. However, even as shallow a deconstruction as the one provided above proves this to be demonstrably not the case. As far as I'm concerned it's perfectly acceptable to dismiss Roth's work because you find his conclusions shallow or abhorrent, but it's an act of pure intellectual laziness to blithely ignore those conclusions and glibly negate the films by classifying them as "Torture Porn" or "Gorno". And by "pure intellectual laziness" I, of course, mean utter stupidity.

Compared to the

Hostel films,

Hard Candy fared a lot better with critics, but not quite as well with several men I happen to know personally—some of who saw the film purely based on my recommendation of it. Considering how much it affected me, I found their reticence towards it somewhat surprising. Whenever I probed them to find out what it was they didn’t like about the film I found they were reluctant to say anything specific, but in each case it eventually became clear that their major problem was with the film’s young, female protagonist.

A two-handed character piece, the film is a psychological thriller about the dangers of online sexual predation, but not quite in the way most people would expect. While Jeff Kohlver (Patrick Wilson) completely matches the profile of one of those idiots regularly caught on camera on

Dateline NBC’s now infamous

“To Catch a Predator” segments (if only a bit smoother, stylish and less obviously creepy) his young prey, Hayley Stark (Ellen Page), is not what you would call a typical 14 year old girl. Not only is she the one who suggests that they meet together after flirting online, but it also soon becomes clear that she is nowhere near as innocent or defenseless as Jeff (and us viewers) assume.

It turns out that Hayley believes Jeff is guilty of a terrible crime and is willing to take dramatic action to ensure he is punished and doesn’t do it again.

Though they were loath to admit it, the reason my male friends refused to praise the film was because it forced them to make a choice they did not want to make—to either sympathize with a man who at best was a sleazy pedophile and at worst a rapist/murderer or the possibly delusional young woman who wanted to cut his balls off. As loathsome as they found Jeff to be, they still could not bring themselves to endorse Hayley’s mission, because—as much as they didn’t want to—they identified with his plight and imagined themselves in his situation.

The more I thought about it, the more it became clear to me that the castration sequence in

Hard Candy is the male equivalent of Camille Keaton’s extended rape in

Day of the Woman (aka

I Spit On Your Grave), not only in terms of length (Jeff spends 34 of the film’s 100 minutes strapped to the table where the “operation” is performed) but also in its ability to shock and divide its audience. As I noted in my

way-too-long discussion of Meir Zarchi’s classic, film critic Roger Ebert denounced

Day of the Woman as the worst film ever made because of his belief that the filmmaker had intended the audience to cheer on the brutal rape of its female protagonist, while it is my belief that Zarchi clearly wanted the audience to be disgusted by what they saw. In much the same way, a person’s appreciation of

Hard Candy depends on whether or not they believe that Hayley is acting rationally and that her actions are just.

There is much evidence to suggest that Jeff is guilty of the crime he is accused of, but it is all circumstantial at best. It also doesn’t help Hayley’s cause that she cruelly toys with him as she makes her surgical preparations. Justice should not be a game and sometimes it seems as though she is having too much fun playing vigilante.

Interestingly, though, one way this sequence differs from Day of the Woman’s rape sequence is that Meir Zarchi leaves nothing to the imagination, while Hard Candy’s David Slade is very careful to obscure what is going on. Of course it later turns out that this is as much for narrative reasons as anything else, but his reticence does little to dull the impact of the sequence, which is the very definition of cringe inducing. Due largely to its length and distressing ambivalence (Slade never allows us to assume that he sympathizes with either character) it is easily the hardest of the sequences discussed in this post for a person to sit through.

That said, I can admit now that unlike my peers who found themselves so troubled by Hayley’s actions they could not enjoy the film, I found myself unwaveringly with her 100% of the time. Part of this is due to the strength of Ellen Page’s performance, which elevated her in my personal pantheon long before everyone caught up with

Juno and part of it is due to my natural instinct to side with fictional female vigilantes, even when they do things I would never advocate a real person (female or otherwise) doing.

Some people find it impossible to separate their personal politics from their enjoyment of a film. For the most part, these are people I try hard to avoid. For me part of the fun of a film like this is that it allows me to embrace a dark side of my own personality I prefer to sublimate in my actual life. Whereas in the world actual I believe there is no room for revenge in the pursuit of justice and therefore abhor capital or physical punishment of any kind (believing that the ultimate form of hypocrisy is for a government to claim that the only way the worst possible crime can be punished is by committing that crime itself), in the cinematic world I am allowed the freedom to embrace my inner redneck and cheer on Hayley as she cuts that pervert’s nuts off.

For this reason I found watching this sequence filled me with both revulsion and exhilaration—I squirmed in sympathy with Jeff, while cheering on Hayley’s act of so-called “preventative maintenance.” As a result for me the truest moment of ambivalence came at the end of the sequence when Jeff, finally left alone, escapes from his bonds and discovers that Hayley has been fucking with him (and, in turn, Slade and screenwriter Brian Nelson, have been fucking with us).

Thus one of the most anxiety provoking castration sequences

in cinematic history is one in which no actual castration occurs at all.

In the final moments of the film, Hayley is able to get Jeff to finally confess his involvement in the crime she has accused him of. He insists that all he did was watch and tells her the name of the real murderer, a man named Aaron. Hayley tells him she's already visited Aaron and that he said the same thing about Jeff. Confronted by his monstrosity and Hayley's (false) assurances that she will keep the one woman he's always loved from discovering his secret, Jeff commits suicide by hanging himself from his roof--a fate that seems almost anti-climatic following his pseudo-castration.

At the end of his extremely well-written and perceptive

review of the film, online genre critic El Santo, points out that another reason--beyond her mere actions--that some people are put off by Hayley's character is her unnatural precocity and near-superhuman abilities, but the reason I didn't find this troubling was because I believed Slade and Nelson inserted subtle clues into the film that suggested that Hayley is not what she appears but rather something supernatural or possibly divine.

When it comes to "accepting" a film, viewers have two options. They can either compare it to the everyday reality they themselves know or they can judge what they see based on the world presented in the film. You can either dismiss Hard Candy out of hand for never explaining how an 80 lb girl can so easily manhandle a man literally twice her size or you can use your imagination and come to your own conclusions on how she is able to do everything she does.

I made my decision in the film's final shot. Though the red hood she wears is an obviously iconic reference to Little Red Riding Hood and her encounter with the Big Bad Wolf (an encounter whose final conclusion differs from telling to telling), I focused more on the look on her face. She had done this before and would do this again, her focus and determination so ineffable that I couldn't help but assume that she was on a mission directly given to her by a vengeful and angry god. It definitely helped when I heard the first word of the song that plays as the screen fades to black and goes to the final credits.

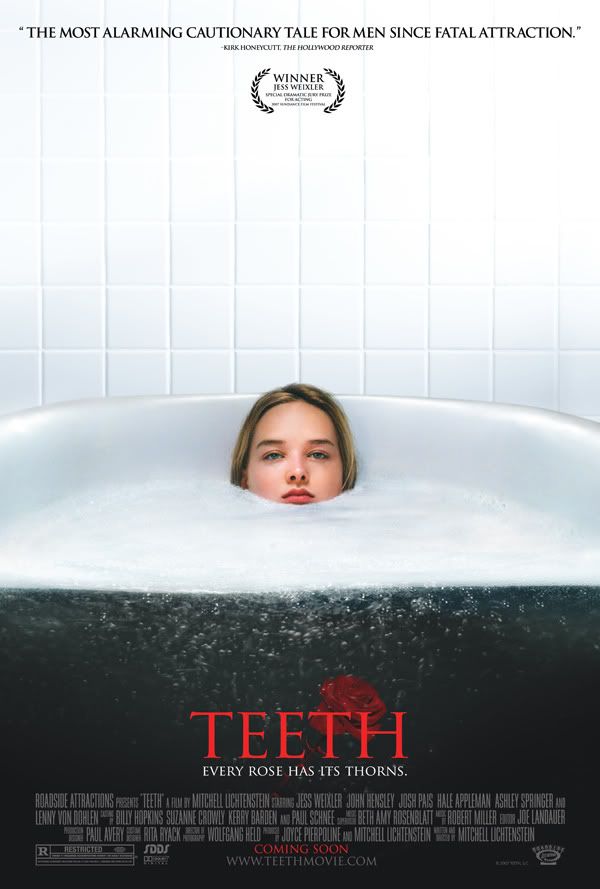

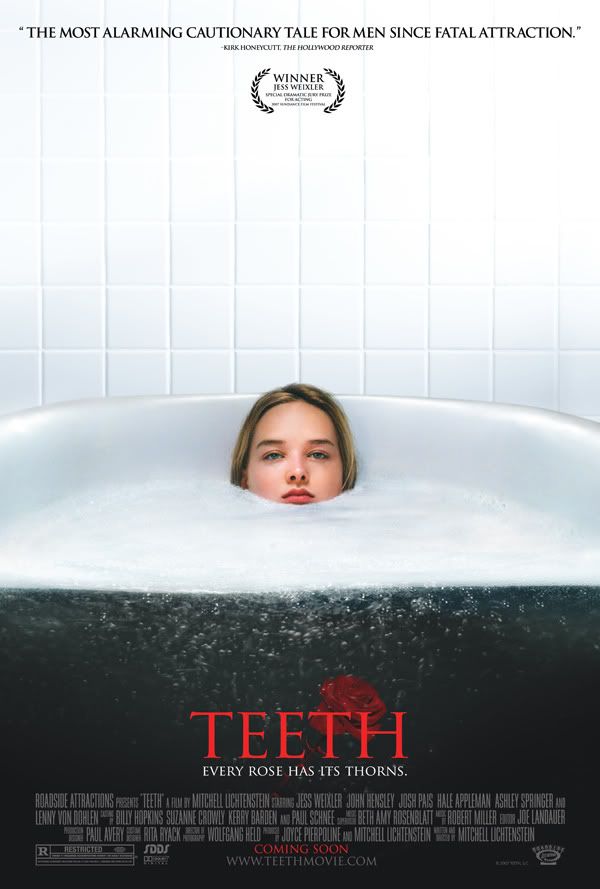

When I say that the last film in this post’s trilogy of modern castration classics surprised me, that is something of an understatement. Not so much for its content—I knew going in what to expect on that end—but by rather how much I enjoyed it. With all apologies to Christopher Nolan,

Teeth remains my pick for best movie I’ve seen this year, although it does seem strange to compare this low-budget combination of horror and comedy to a project as monolithic as

The Dark Knight.

The film’s most immediate cinematic peer is the justly heralded cult classic

Ginger Snaps, which remains one of my favourite films from this decade. Both are horror tales about young female outcasts whose ascent into womanhood turns deadly due to forces within their own bodies they cannot control. In

Ginger Snaps, that force is the lycanthropy that causes young Ginger to embrace her carnal side as she descends into a state of permanent beastliness, while in

Teeth it is the virginal Dawn’s discovery that she is the flesh and blood incarnation of one of the Earth’s oldest and most widespread myths.

One of the things I loved most about Mitchell Lichtenstein’s script is the risk he takes in making his protagonist a character most horror movies fans by nature would abhor—an abstinence-preaching goodie-goodie who wears her virginity on her sleeve and hangs out with friends so pious they refuse to see an R-rated movie. In less deft hands Dawn (Jess Wexler) could have turned out to be as obnoxious a character as Mandy Moore’s in the supremely tiresome

A Walk to Remember (not to be confused with her deliberately obnoxious character in the brilliant

Saved!), but in one short sequence he gains her our sympathy by showing us that she is just as much an outcast as any black-shirted malcontent.

As audacious as Lichtenstein’s choice is, it does make perfect narrative sense, insofar as Dawn’s veneration of her own virtue explains away the story's potential biggest plot hole. By making her essentially afraid of her own sexuality (as exemplified by her horrified reactions to her intensely erotic dreams) it becomes possible to appreciate how she has been able to avoid any potential physical examination that would expose her strange mutation.

Though the cause of this mutation is most likely linked to the presence of the enormous nuclear cooling tower visible just a few miles from her house (as is the cancer slowing killing her mother) Lichtenstein’s script also suggests that it is a natural evolutionary step—one that is necessary if women are ever to wrest themselves from the physical dominance of brutal, sex-obsessed males.

If ever there was a subject begging to be exploited in a horror movie setting, Vagina dentata has to take first prize. While it has been used as a subtext (both consciously and accidentally) in many films, Teeth is one of the first to chuck metaphor out the window in favour of a direct representation of man’s biggest unspoken fear. It’s genius, though, comes in the way it allows us to subvert that fear and compels us to cheer on the young woman who is the unwitting symbol of primal emasculation. Rather than terrify us with a horrific descent into Dawn’s monstrosity, Lichtenstein chooses to create a story of empowerment in which Dawn’s mutation makes the slow transformation from inexplicable curse to exploitable gift.

Like Roth, Lichtenstein’s intentions are clearly satirical, which means its characters have been drawn to serve his thematic purposes rather than serve as three-dimensional representations of people found in our own non-cinematic reality. That said it does seem only fair that in a film where its female protagonist is partially defined by the devastating power of her vagina, all of the male characters are shown to be incapable of making any decision not immediately linked to the desires of their penises. In the world of

Teeth, every male is a potential sexual predator, especially the nice ones who say all the right things.

This is a completely accurate depiction of the world as it really is.

I don’t mean to propagate the hoary old feminist cliché that every man is a wannabe rapist, but rather that the biological impulse to procreate remains strong enough that few men possess the inner-strength to ever completely disregard it. In Teeth this is best represented by the character Tobey (Hale Appleman), a fellow “abstainer” whose chaste flirtations with Dawn quickly escalates into violence as a result of his own pent-up sexual frustration (“I haven’t even jerked off since Easter,” he shouts at her in an attempted mitigation of his assault). During this, her first experience with intercourse, Dawn and Tobey both discover her hidden secret and following his entirely unexpected castration, he falls into the water they had been swimming in and does not come back up to the surface.

With this Dawn is not only forced to contemplate her mutation, but also her own sexuality for the first time in her life. This leads to her first ever visit to a gynecologist in a scene that best exemplifies the film’s darkly humourous tone. Perhaps it says something about my own twisted sense of humour, but I laughed longer and harder the first time I watched this moment than during any other scene I’ve seen this year.

With this second incident a clear pattern begins to emerge. Sensing Dawn’s unusual innocence, the men around her seek to exploit her sexual naiveté only to find out too late that they do so at their peril. Though she lacks the experience to immediately recognize the inappropriateness of the doctor’s actions (his gloveless probing clearly treading past the line from routine examination into outright molestation), subconsciously she identifies the violation for what it is and her body takes action against it. As will become clear with her next sexual experience, her strange “adaptation” does not act in opposition to her impulses, but directly with them. Though she does not know it yet, she is in complete control of her sexuality—it is merely a matter of accepting and embracing it.

Overcome by her role in Tobey’s death, the doctor’s mutilation and her mother’s collapse and subsequent hospitalization, Dawn finds herself drawn to Ryan (Ashley Springer), a boy from school whose crush on her has always been flagrantly apparent. He does his best to comfort her anxiety (including giving her some pills purloined from his mother), while also exploiting her duress for his benefit. He decorates his room with candles and gives her wine, having correctly identified the romantic tropes she associates with the abdication of her virginity. Touched by his gentleness and attention, Dawn engages with him in her first act of consensual intercourse and is shocked to find that when it ends he is none the worse for it. Afterwards she examines her topless body in the mirror and already a new self-confidence is apparent in her bearing and demeanor. In that moment she makes the visible transition from being a girl to becoming a woman, which makes what happens next all the more powerful.

About to leave, she is drawn back to Ryan’s bed for one more round of coitus, only to find out—via a phone call from his friend—that he has just successfully won a bet in which he would be the first to claim the pretty virgin’s maidenhood. In that moment the last vestige of her innocence is extinguished for good and Ryan promptly meets the same painful fate of Tobey and the bad doctor. Her reaction here is telling. No longer terrified of what she can do, all she can muster in way of a response is a comic “Oh shit,” as she dismounts Ryan and leaves him screaming in his bed. “Some hero,” she mutters to herself, having learned the truth behind her girlish romantic fantasies.

It’s interesting to note the degree to which the film allows its male "victims" to suffer. As a full-on rapist, Tobey’s punishment is death. The doctor, whose assault—while creepy—was not as violent or as obvious as Tobey’s is shown having his fingers reattached, but is also dramatically traumatized by the incident (“Vagina dentata,” he keeps repeating, “it’s real….”). Ryan’s initial tenderness is “rewarded” in that he survives the encounter and is—like the doctor—shown having his severed organ reattached to his body, although he too will doubtlessly be traumatized for life. Of them all it is her final “victim”—her stepbrother, Brad—who is punished with the worst of all the possible fates (at least from a decidedly male viewpoint).

Dawn’s opposite in every way, Brad’s callousness is the direct result of his resentment over the marriage of his father to Dawn’s mother. Not because of any lingering devotion to his own mother, but rather because of his feelings for Dawn. By making her his sister, the marriage prevented him from ever being able to act upon his sexual desire for her in a socially acceptable manner. For this reason when he hears his cancer-ridden stepmother collapse in the hallway, he ignores her cries and leaves her to be found by Dawn, who goes on to blame him for her subsequent death.

With this Dawn comes to realize that her “adaptation” is not a deformity, but rather an aspect of herself with which she can extract karmic justice. She goes on to visit Brad in his room, dressed for seduction (albeit in a manner that reflects her goodie-goodie instincts) and proceeds to deliberately do to him what she unintentionally did to the others. His suffering continues when Dawn defiantly drops his severed member onto his floor, only to watch as his pit bull escapes from its cage and proceeds to eat it in a couple of quick bites. Unlike Tobey, who didn’t live long enough to appreciate what had happened to him, or Ryan, whose mutilation was only temporary, Brad is shown being completely robbed of his manhood without any chance for recovery.

The film then ends with Dawn leaving her small town by hitchhiking out on the highway, And as much as I enjoyed everything that came before it, it is the film’s last scene that truly won me over. Trapped in the car with an obnoxious old pervert, Dawn is first annoyed by the situation, but that annoyance visibly dissipates when she realizes that she, not he, is the one who is truly in control of what is going on. Her smile at this awareness made me doing something I

never do when I watch a movie—applaud. It was the only response I could think of to justify how good it made me feel.

Of all the films, Teeth is the most graphic in its depiction of its castrations. Though, unlike Hostel: Part II, we never actually see Dawn sever the penises from her “victims” bodies, we are exposed to much longer takes of the various aftermaths. Yet it remains the least discomfiting of the three films, largely because rather than acts of overt hostility, its castrations are presented either as an unconscious reaction to an assault or emotional betrayal or—in the last case—a just act of revenge committed against an utter douchebag. This is interesting in that it suggests that the power of onscreen violence has little to do with what we are actually shown onscreen but instead by how what we are being shown makes us feel. Though some would suggest this serves as a good argument in defense of restraint, one could easily argue with just as much validity that the degree to which graphic violence is acceptable depends on how the filmmaker intends their audience to react when they see it. In other words, it is foolish to suggest that one approach is better than the other when it all depends on the context in which they are used.

And that folks is my way-too-long look at a recent cinematic phenomenon only a freak like me would ever think to document. It only took me two months to throw it all together and I'm already fairly certain it wasn't worth the wait....

The film is 1980s You Better Watch Out (or, as it is better known, Christmas Evil) and though the film bears a superficial resemblence to the more infamous Silent Night, Deadly Night, they are actually as different as two films about homicidal maniacs in Santa suits could be. You Better Watch Out is actually closer in spirit to films like Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver and Roman Polanski's Repulsion than it is to a traditional slasher movie. Rather than being a movie about a madman's killing spree, it is instead about what has led that madman to go on that spree in the first place. Stylistically it is the kind of raw and dirty movie that defined the cinema of the 70s. It's one of those movies where its obvious low budget and grainy cinematography adds to rather than subtracts from its sense of realism, which only makes its surreal ending that much more thrilling to watch.

The film is 1980s You Better Watch Out (or, as it is better known, Christmas Evil) and though the film bears a superficial resemblence to the more infamous Silent Night, Deadly Night, they are actually as different as two films about homicidal maniacs in Santa suits could be. You Better Watch Out is actually closer in spirit to films like Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver and Roman Polanski's Repulsion than it is to a traditional slasher movie. Rather than being a movie about a madman's killing spree, it is instead about what has led that madman to go on that spree in the first place. Stylistically it is the kind of raw and dirty movie that defined the cinema of the 70s. It's one of those movies where its obvious low budget and grainy cinematography adds to rather than subtracts from its sense of realism, which only makes its surreal ending that much more thrilling to watch.

It comes as no surprise that Harry's strange hobby wrecks havoc on his social life. He has no friends and is mocked as a loser by his co-workers. The neighborhood kids are charmed by his own childlike demeanor, but he wisely keeps his distance from them. His only real contact with the world comes from his brother's family, but as the film begins Harry has already started the inexorable journey from eccentricity to madness and he starts avoiding them as well. At work he becomes angry when he discovers that the owner's pledge to donate toys to a local hospital for disable children is purely a publicty stunt and very few toys are actually going to make it into the children's hands. Having already started to design his own ornate Santa Claus costume, Harry decides to correct his company's fraud by stealing toys from the factory floor and giving them to the hospital himself. To add authenticity to his delivery, he takes the time to paint the image of a sled on the side of his van.

It comes as no surprise that Harry's strange hobby wrecks havoc on his social life. He has no friends and is mocked as a loser by his co-workers. The neighborhood kids are charmed by his own childlike demeanor, but he wisely keeps his distance from them. His only real contact with the world comes from his brother's family, but as the film begins Harry has already started the inexorable journey from eccentricity to madness and he starts avoiding them as well. At work he becomes angry when he discovers that the owner's pledge to donate toys to a local hospital for disable children is purely a publicty stunt and very few toys are actually going to make it into the children's hands. Having already started to design his own ornate Santa Claus costume, Harry decides to correct his company's fraud by stealing toys from the factory floor and giving them to the hospital himself. To add authenticity to his delivery, he takes the time to paint the image of a sled on the side of his van.

The news quickly spreads that a homicidal Santa is rampaging through the streets of the unnamed city. The police organize a lineup of suspects, but Harry is not among them. Armed with a sackful of toys he returns to his neighborhood and starts handing out presents to the kids, which immediately arouses the suspicions of his neighbors. One of them threatens Harry with bodily harm, but he is stopped when the kids intervene and allow their benefactor to escape in his van. As he drives to his brother's house, a mob (complete with torches!) forms and begins to search the streets for him. His brother is horrified to discover that Harry is the madman responsible for all of the mayhem being reported on TV. They end up coming to blows and his brother strangles Harry until he is unconscious. Afraid that he has killed him, he puts Harry back into the van, only to discover that Santa still has some life in him yet.

The news quickly spreads that a homicidal Santa is rampaging through the streets of the unnamed city. The police organize a lineup of suspects, but Harry is not among them. Armed with a sackful of toys he returns to his neighborhood and starts handing out presents to the kids, which immediately arouses the suspicions of his neighbors. One of them threatens Harry with bodily harm, but he is stopped when the kids intervene and allow their benefactor to escape in his van. As he drives to his brother's house, a mob (complete with torches!) forms and begins to search the streets for him. His brother is horrified to discover that Harry is the madman responsible for all of the mayhem being reported on TV. They end up coming to blows and his brother strangles Harry until he is unconscious. Afraid that he has killed him, he puts Harry back into the van, only to discover that Santa still has some life in him yet. Awhile back a friend from my old job mentioned to me that she had recently rented the 1981 holiday slasher flick My Bloody Valentine and remarked that she had been surprised to find out that it was Canadian. Being the obnoxious geek that I am, I explained to her that it must have been one of the infamous "Tax-Shelter Films" from that period.

Awhile back a friend from my old job mentioned to me that she had recently rented the 1981 holiday slasher flick My Bloody Valentine and remarked that she had been surprised to find out that it was Canadian. Being the obnoxious geek that I am, I explained to her that it must have been one of the infamous "Tax-Shelter Films" from that period. But unlike most of the films from this strange period in Canadian cinema, My Bloody Valentine stands out because rather than deny its Northern origins, it embraces them almost to the point of unintended self-parody. Fearful of alienating American audiences, the majority of films shot in Canada (even to this day) are either set in specific American locales or in nameless, unidentified places where all hints of Canadiana are carefully kept away from the camera. This is definitely not the case with this film, though, as it could very well be THE MOST EXPLICITLY CANADIAN MOVIE EVER MADE. Seriously, the only way the movie could be more Canadian would be if the killer turned out to be a beaver in a hockey mask who killed his victims by stuffing Timbits down their throats. And in case any movie producers are reading this, THAT is a movie I would very much like to see.

But unlike most of the films from this strange period in Canadian cinema, My Bloody Valentine stands out because rather than deny its Northern origins, it embraces them almost to the point of unintended self-parody. Fearful of alienating American audiences, the majority of films shot in Canada (even to this day) are either set in specific American locales or in nameless, unidentified places where all hints of Canadiana are carefully kept away from the camera. This is definitely not the case with this film, though, as it could very well be THE MOST EXPLICITLY CANADIAN MOVIE EVER MADE. Seriously, the only way the movie could be more Canadian would be if the killer turned out to be a beaver in a hockey mask who killed his victims by stuffing Timbits down their throats. And in case any movie producers are reading this, THAT is a movie I would very much like to see. From the general hoser behaviour of its characters, the maple syrup thick Canadian accents (I swear I actually heard several examples of the fabled "a-boot"), the constant references to

From the general hoser behaviour of its characters, the maple syrup thick Canadian accents (I swear I actually heard several examples of the fabled "a-boot"), the constant references to

As the film's requisite Creepy Old Man tells the skeptical young miners who hang out in his bar, there's a reason why the town hasn't held a Valentine's Day dance in 20 years. It all began when two foreman--eager to leave work so they could get cleaned up and go to the dance--left six miners alone in the mine, all of whom were trapped when a methane leak caused an explosion. It took six weeks to clean up the rubble and only one of the six miners was found alive. Harry Warden, having lost his mind during the ordeal, resorted to cannibalism to survive and was more than a little pissed at the two foreman who left him and his friends alone in the mine that Valentine's Day. Wearing his workclothes, he killed the two men with a pick-ax befor being caught and sent to the nearby mental hospital. Since then all of the town's Valentine's festivities had been canceled, out of fear Harry might escape and return to mete out further vengeance against the town. But after two decades the story of the killer miner has become the stuff of boogeyman legend and everyone assumes it is safe to start celebrating the holiday of love once again. It goes without saying that they are mistaken.

As the film's requisite Creepy Old Man tells the skeptical young miners who hang out in his bar, there's a reason why the town hasn't held a Valentine's Day dance in 20 years. It all began when two foreman--eager to leave work so they could get cleaned up and go to the dance--left six miners alone in the mine, all of whom were trapped when a methane leak caused an explosion. It took six weeks to clean up the rubble and only one of the six miners was found alive. Harry Warden, having lost his mind during the ordeal, resorted to cannibalism to survive and was more than a little pissed at the two foreman who left him and his friends alone in the mine that Valentine's Day. Wearing his workclothes, he killed the two men with a pick-ax befor being caught and sent to the nearby mental hospital. Since then all of the town's Valentine's festivities had been canceled, out of fear Harry might escape and return to mete out further vengeance against the town. But after two decades the story of the killer miner has become the stuff of boogeyman legend and everyone assumes it is safe to start celebrating the holiday of love once again. It goes without saying that they are mistaken. Given the nature of the holiday the movie is centered around, it's only natural that a part of its plot is devoted to a love triangle. T.J., the film's nominal hero (if only because he manages to survive all the way to the end) is the mayor's son who has returned to the town after failing to make it on his own "out west." During his absence he left behind Sarah (who also survives, but can't accurately be described as a proper Final Girl) who--never knowing if or when T.J. was going to return--started dating Axel. Sarah is clearly torn between the man who left her and now wants her back and the man who's been with her ever since T.J. went away, while the audience has trouble figuring out why she's attracted to either of them. I suspect many folks will find these more dramatic sequences difficult to sit through, but I found myself much taken by the low-rent

Given the nature of the holiday the movie is centered around, it's only natural that a part of its plot is devoted to a love triangle. T.J., the film's nominal hero (if only because he manages to survive all the way to the end) is the mayor's son who has returned to the town after failing to make it on his own "out west." During his absence he left behind Sarah (who also survives, but can't accurately be described as a proper Final Girl) who--never knowing if or when T.J. was going to return--started dating Axel. Sarah is clearly torn between the man who left her and now wants her back and the man who's been with her ever since T.J. went away, while the audience has trouble figuring out why she's attracted to either of them. I suspect many folks will find these more dramatic sequences difficult to sit through, but I found myself much taken by the low-rent  Beyond that the film features the standard authority figures trying to keep the return of the murdering maniac a secret, the young adults defying the authority figures and throwing the party anyway and the shocking discovery that the killer isn't who everyone thinks it is. The gore is kept to a minimum and the filmmakers show an unfortunate restraint in their presentation of sex and nudity. Unlike most slasher movie victims, who at least get to enjoy penetration and/or a climax before they are killed, all of the amorous folks in this movie get whacked before they can even get past second base. And those folks who actually expect a movie like this to be frightening (which I've never really understood, but anyway...) will likely be disappointed as director George Milhalka keeps the action as predictable and suspense-free as possible. Despite this, anyone interested in seeing a completely straight-faced version of

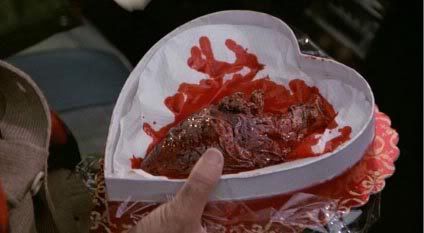

Beyond that the film features the standard authority figures trying to keep the return of the murdering maniac a secret, the young adults defying the authority figures and throwing the party anyway and the shocking discovery that the killer isn't who everyone thinks it is. The gore is kept to a minimum and the filmmakers show an unfortunate restraint in their presentation of sex and nudity. Unlike most slasher movie victims, who at least get to enjoy penetration and/or a climax before they are killed, all of the amorous folks in this movie get whacked before they can even get past second base. And those folks who actually expect a movie like this to be frightening (which I've never really understood, but anyway...) will likely be disappointed as director George Milhalka keeps the action as predictable and suspense-free as possible. Despite this, anyone interested in seeing a completely straight-faced version of  Also released as Rosemary's Killer in Europe, The Prowler is best remembered today for featuring some of Tom Savini's more memorable slasher movie make-up effects and for being the film that got director Joseph Zito the job of putting together the

Also released as Rosemary's Killer in Europe, The Prowler is best remembered today for featuring some of Tom Savini's more memorable slasher movie make-up effects and for being the film that got director Joseph Zito the job of putting together the

For reasons that are left to the audience's imaginations rather than actually explained, the never-caught psycho ex-soldier responsible for the murders that night 35 years earlier decides to suit up once again and arm himself with a bayonet, a sawed-off shotgun and his trusty pitchfork. He then proceeds to make his way to the almost-vacant dorm rooms and finds a young couple who are just about to get squishy with it. The young man gets a bayonet in the head and his naked girlfriend gets pitchforked in the shower.

For reasons that are left to the audience's imaginations rather than actually explained, the never-caught psycho ex-soldier responsible for the murders that night 35 years earlier decides to suit up once again and arm himself with a bayonet, a sawed-off shotgun and his trusty pitchfork. He then proceeds to make his way to the almost-vacant dorm rooms and finds a young couple who are just about to get squishy with it. The young man gets a bayonet in the head and his naked girlfriend gets pitchforked in the shower.

From that point on the movie does what its supposed to do and intercuts scenes of The Prowler killing folks with Pam and Mark trying to figure out what is going on. The script does try to be a bit different by ignoring some of the more blatent cliches. For example one couple (who ultimately serve absolutely no purpose to the film's narrative) are allowed to have sex without dying and the male protagonist is allowed to remain alive. But even here the picture is a bit clumsy, since we are lead to believe The Prowler has killed Mark, but he is shown to be alive and unharmed after Pam finally manages to kill the murderer in typical Final Girl fashion. This could have been cleared up with a single line of dialogue, but the filmmakers seem too eager to get to the film's last shocking surprise (which ends up being neither shocking or surprising) to bother tying up such an obvious loose end.

From that point on the movie does what its supposed to do and intercuts scenes of The Prowler killing folks with Pam and Mark trying to figure out what is going on. The script does try to be a bit different by ignoring some of the more blatent cliches. For example one couple (who ultimately serve absolutely no purpose to the film's narrative) are allowed to have sex without dying and the male protagonist is allowed to remain alive. But even here the picture is a bit clumsy, since we are lead to believe The Prowler has killed Mark, but he is shown to be alive and unharmed after Pam finally manages to kill the murderer in typical Final Girl fashion. This could have been cleared up with a single line of dialogue, but the filmmakers seem too eager to get to the film's last shocking surprise (which ends up being neither shocking or surprising) to bother tying up such an obvious loose end.

For example, there’s the famous scene in

For example, there’s the famous scene in