Repost - The Big Hurt

Once upon a time a person could reasonably expect that whenever they went to see a movie one of the last things they would ever have to watch was the sight of a man’s penis being forcibly removed from his body.

In the past few years a handful of filmmakers have taken it upon themselves to break what could be consider one of the last remaining cinematic taboos and deliver unto their audiences startlingly graphic depictions of castration. Now that’s not to say they were the first to do this, as the history of exploitation cinema is peppered with titles that were willing to take aim straight at the area responsible for their male audiences’ most common and immediate fears.

For example, there’s the famous scene in Ilsa, She-Wolf of the S.S., in which the title character (memorably played by the unforgettable Dyanne Thorne) informs her now-former lover that it is her habit to neuter a man once he is no longer able to satisfy her insatiable sexual demands and then goes on to prove it with a very sharp surgical implement (an act that allows for the irony of her eventually being undone by his replacement, a Polish soldier whose priapism leads to her finally meeting her match). Although the scene is nowhere near as graphic as the ones about to be discussed, it is interesting insofar as it’s the one significant act of violence against a male character in a film whose central theme is literally built upon the presentation of violence against women (Ilsa’s pet theory being that women are naturally capable of absorbing more pain than men, which she attempts to prove by inflicting a series of graphic tortures against every busty soft-core actress who was working in 1975). One gets the sense that by presenting us with what most would consider the ultimate form of brutality that can be committed against a man, the filmmakers were hoping to offset the blatant misogyny of the rest of the film.

For example, there’s the famous scene in Ilsa, She-Wolf of the S.S., in which the title character (memorably played by the unforgettable Dyanne Thorne) informs her now-former lover that it is her habit to neuter a man once he is no longer able to satisfy her insatiable sexual demands and then goes on to prove it with a very sharp surgical implement (an act that allows for the irony of her eventually being undone by his replacement, a Polish soldier whose priapism leads to her finally meeting her match). Although the scene is nowhere near as graphic as the ones about to be discussed, it is interesting insofar as it’s the one significant act of violence against a male character in a film whose central theme is literally built upon the presentation of violence against women (Ilsa’s pet theory being that women are naturally capable of absorbing more pain than men, which she attempts to prove by inflicting a series of graphic tortures against every busty soft-core actress who was working in 1975). One gets the sense that by presenting us with what most would consider the ultimate form of brutality that can be committed against a man, the filmmakers were hoping to offset the blatant misogyny of the rest of the film.

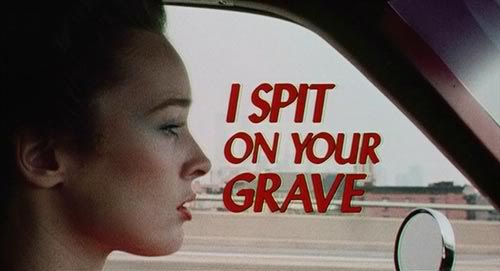

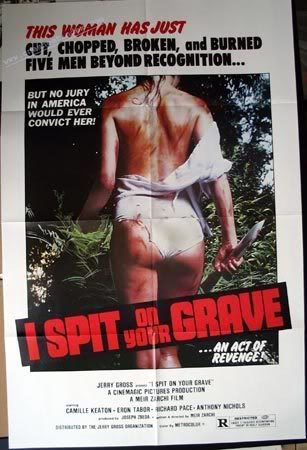

And, of course, there’s the scene I discussed in Day of the Woman where Camille Keaton gets revenge for her vicious, extended gang-rape by cutting off the junk of the guy who made it happen, as well as several more examples I’m too lazy to mention because if I did I’d have to link to their IMDb pages and that takes more time and effort than you’d ever think it would. So, yes, there is a precedent of cinematic castration throughout the history of the art, but it’s only in the past few years that filmmakers have been so increasingly happy to take it to the furthest possible cringe-inducing level.

The reality is that my interest in this recent phenomenon has less to do with any natural fascination with castration (I am, after all, a man and I happen to revere my phallus as much as any other Tom, Dick or Harry), but rather with the characters shown to be doing the castrating. One is a wealthy young woman who is driven to commit her violent act as a desperate means of survival. Another is a girl whose motives and identity are so clouded in mystery it’s possible to assume she’s not even human, but instead a divine angel of vengeance sent forth to avenge a terrible crime. And the last is a true innocent whose strange “adaptation” turns her into the living embodiment of one of the world’s oldest and most universal of myths. All three of them begin their stories as victims, but end them stronger than they were before—proving that the most extreme feminists were right, female empowerment really is just a matter of slicing off some dick's dick.

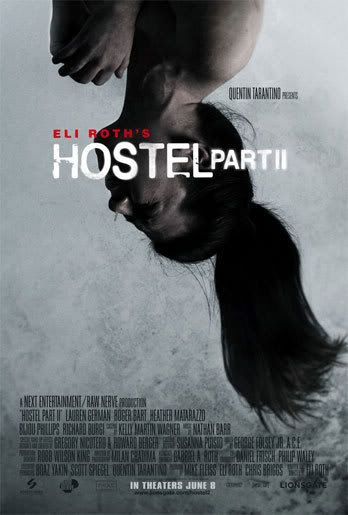

When I say that I am stunned and perplexed by the reaction Eli Roth’s Hostel: Part II received when it was released, I am speaking just as much as the serious cineste who can spend hours talking about the films of the usual gang of European arthouse auteurs as I am the genre enthusiast who’s devoted hours of his life deconstructing the thematic intricacies of Slumber Party Massacre II. While my low-opinion of mainstream critics allowed me to expect that they would lack the insight to look beyond its premise and controversially graphic torture set pieces, I was shocked when many genre fans equally failed to grasp how successfully it worked as a sophisticated piece of Swiftian style satire. Rather than acknowledge the interesting themes Roth chose to explore in this second film, both groups focused solely on its scenes of violence and dubbed the film a mere gender-reversed replica of the original.

But I would argue that by simply reversing the genders of his protagonists, Roth created what was both an inherently more interesting and thematically insightful film. Whereas the first film focused on the irony of foreign tourists who use their wealth to exploit people in other countries, only to themselves become much more heinously exploited by far wealthier tourists with much more depraved tastes, the second takes a broader look at the global society in which such an underground industry could actively flourish. In Hostel it is easy to imagine that had he not been lured into the enterprise as a victim, Jay Hernandez’s character, Paxton, would eventually grow up to become one of its customers, if only because of his stereotypical alpha-male tendencies and willingness to use the misfortune of others as a means to satisfy his own carnal pleasures. The same cannot be said for Beth (Laura Germain) the second film’s protagonist, who—largely by virtue of her femininity—is infinitely more sympathetic and vulnerable than her predecessor, which makes her final transformation that much more dramatic and interesting.

For those of you who have yet to see either film, both are about a small town in Slovakia whose local economy revolves around luring young tourists into their quaint hostel, where they are subsequently kidnapped and sent to an abandoned Soviet-era concrete monstrosity. There they are sold to wealthy businessmen who travel from across the world for the opportunity to enjoy the experience of torturing and killing another person without consequence. While for most viewers the horror in both films lies in their graphic depictions of torture, I personally feel this is strongly superseded by the both the existence of the enterprise that allows this torture to happen and its apparent popularity. As far as I’m concerned the most chilling sequence of the two films occurs in Part II, just after Beth and her two friends, Lorna and Whitney, have arrived at the titular hostel and—without their knowing it—have become the objects of desire in an international bidding war over the right to maim and kill them.

Watching the two friends interact it’s hard not to think of the two similar characters in Neil LaBute’s directorial debut In the Company of Men who decide to avenge their frustrations towards women by deliberately humiliating the most innocent woman they can find. Todd (Richard Burgi) is the ringleader and alpha-male, while Stuart (Roger Bart) is the follower, who reluctantly goes along on the trip despite his grave moral concerns about what they are doing. In that way they also resemble the two main protagonists from the first film, Paxton and Josh (Derek Richardson). The clear subtext in the first Hostel was that Josh allowed himself to be ordered around by his more dominant friend because their manly adventures allowed him to avoid confronting his own closeted homosexuality, while in Part II Stuart follows Todd because their adventures together (all of which the far-wealthier Todd pays for) represent the only times in his life where he is able to escape the stifling bonds of his career and familial obligations.

But as their stories continue and the two friends at last find themselves in their leather butcher aprons and alone with the women they are now contractually obligated to murder (the organization’s secrecy is maintained by a kind of mutually assured destruction in which everyone who takes part is as guilty as everyone else) the true nature of their personalities come out. Todd, the pure hedonist, who has dressed Whitney in the costume of a low-rent prostitute, at first seems to enjoy the experience, teasing his victim with a circular saw. But when he slips and the weapon connects with her face and does actual damage, the seriousness and horror of the situation finally dawns on him. Suddenly aware that this is not a game and that he is in a room with a real human being who screams and bleeds when she is injured, he panics and runs out of the room. Informed that he must finish her off in order to meet his obligation, he refuses and is then mauled to death by a group of dogs kept around for just such occasions.

Stuart’s first instincts, on the other hand, are to attempt to rescue Beth—who he has dressed in the casual business attire worn by the women in his day-to-day life—but as the reality of the situation becomes more apparent to him he realizes he really does want to kill her. Finally given a true outlet for all of the frustrations and humiliations he has swallowed down over the years, he realizes he actually relishes the chance to take it. Given the opportunity to finish off Whitney for a reasonable discount, he happily decapitates her with a machete before returning to Beth, who has come to represent in his mind all of the women who have embarrassed and "castrated" him throughout his life.

More than anything it is her journey that I feel elevates Hostel: Part II to a far greater level than its detractors allow. A very wealthy young woman following the death of her father, Beth has not only the will but also the resources required to be a kind and generous person. Far more sensible than her party-girl friend Whitney, but also more cautious than the naïve Lorna, Beth is the most grounded and centered character in the film (her one quirk being her very strong and visceral reaction to anyone who calls her the dreaded c-word). For this reason she is able to keep her head and figure out a way out of the torture chamber fate has thrown her into. When Stuart returns to kill her, she is able to reverse their situations and attempts to bargain her way out with the man in charge. The fate of his manhood (and life) literally in her hands, Stuart is unable to contain his rage and says the one thing guaranteed to ensure his emasculation.

A two-handed character piece, the film is a psychological thriller about the dangers of online sexual predation, but not quite in the way most people would expect. While Jeff Kohlver (Patrick Wilson) completely matches the profile of one of those idiots regularly caught on camera on Dateline NBC’s now infamous “To Catch a Predator” segments (if only a bit smoother, stylish and less obviously creepy) his young prey, Hayley Stark (Ellen Page), is not what you would call a typical 14 year old girl. Not only is she the one who suggests that they meet together after flirting online, but it also soon becomes clear that she is nowhere near as innocent or defenseless as Jeff (and us viewers) assume.

It turns out that Hayley believes Jeff is guilty of a terrible crime and is willing to take dramatic action to ensure he is punished and doesn’t do it again.

Though they were loath to admit it, the reason my male friends refused to praise the film was because it forced them to make a choice they did not want to make—to either sympathize with a man who at best was a sleazy pedophile and at worst a rapist/murderer or the possibly delusional young woman who wanted to cut his balls off. As loathsome as they found Jeff to be, they still could not bring themselves to endorse Hayley’s mission, because—as much as they didn’t want to—they identified with his plight and imagined themselves in his situation.

The more I thought about it, the more it became clear to me that the castration sequence in Hard Candy is the male equivalent of Camille Keaton’s extended rape in Day of the Woman (aka I Spit On Your Grave), not only in terms of length (Jeff spends 34 of the film’s 100 minutes strapped to the table where the “operation” is performed) but also in its ability to shock and divide its audience. As I noted in my way-too-long discussion of Meir Zarchi’s classic, film critic Roger Ebert denounced Day of the Woman as the worst film ever made because of his belief that the filmmaker had intended the audience to cheer on the brutal rape of its female protagonist, while it is my belief that Zarchi clearly wanted the audience to be disgusted by what they saw. In much the same way, a person’s appreciation of Hard Candy depends on whether or not they believe that Hayley is acting rationally and that her actions are just.

There is much evidence to suggest that Jeff is guilty of the crime he is accused of, but it is all circumstantial at best. It also doesn’t help Hayley’s cause that she cruelly toys with him as she makes her surgical preparations. Justice should not be a game and sometimes it seems as though she is having too much fun playing vigilante.

Some people find it impossible to separate their personal politics from their enjoyment of a film. For the most part, these are people I try hard to avoid. For me part of the fun of a film like this is that it allows me to embrace a dark side of my own personality I prefer to sublimate in my actual life. Whereas in the world actual I believe there is no room for revenge in the pursuit of justice and therefore abhor capital or physical punishment of any kind (believing that the ultimate form of hypocrisy is for a government to claim that the only way the worst possible crime can be punished is by committing that crime itself), in the cinematic world I am allowed the freedom to embrace my inner redneck and cheer on Hayley as she cuts that pervert’s nuts off.

For this reason I found watching this sequence filled me with both revulsion and exhilaration—I squirmed in sympathy with Jeff, while cheering on Hayley’s act of so-called “preventative maintenance.” As a result for me the truest moment of ambivalence came at the end of the sequence when Jeff, finally left alone, escapes from his bonds and discovers that Hayley has been fucking with him (and, in turn, Slade and screenwriter Brian Nelson, have been fucking with us).

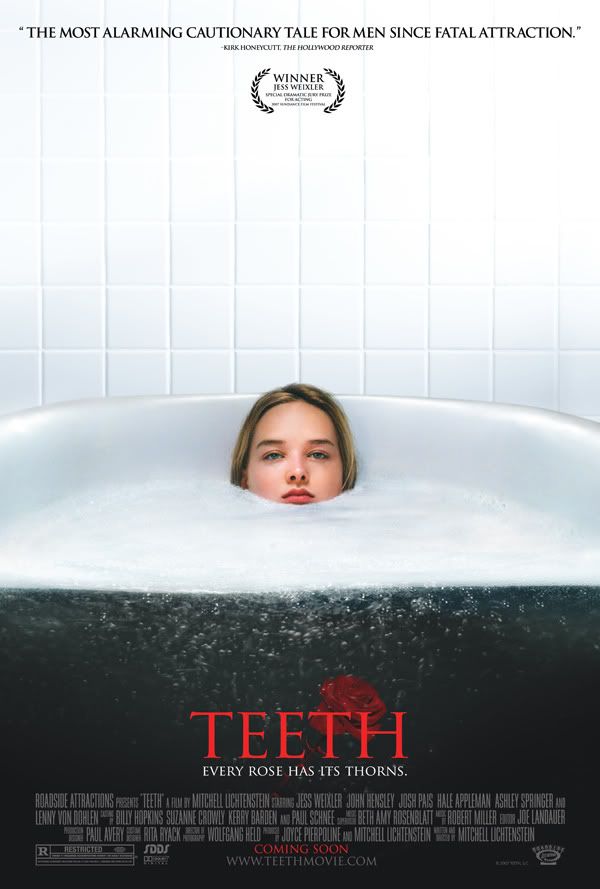

The film’s most immediate cinematic peer is the justly heralded cult classic Ginger Snaps, which remains one of my favourite films from this decade. Both are horror tales about young female outcasts whose ascent into womanhood turns deadly due to forces within their own bodies they cannot control. In Ginger Snaps, that force is the lycanthropy that causes young Ginger to embrace her carnal side as she descends into a state of permanent beastliness, while in Teeth it is the virginal Dawn’s discovery that she is the flesh and blood incarnation of one of the Earth’s oldest and most widespread myths.

One of the things I loved most about Mitchell Lichtenstein’s script is the risk he takes in making his protagonist a character most horror movies fans by nature would abhor—an abstinence-preaching goodie-goodie who wears her virginity on her sleeve and hangs out with friends so pious they refuse to see an R-rated movie. In less deft hands Dawn (Jess Wexler) could have turned out to be as obnoxious a character as Mandy Moore’s in the supremely tiresome A Walk to Remember (not to be confused with her deliberately obnoxious character in the brilliant Saved!), but in one short sequence he gains her our sympathy by showing us that she is just as much an outcast as any black-shirted malcontent.

As audacious as Lichtenstein’s choice is, it does make perfect narrative sense, insofar as Dawn’s veneration of her own virtue explains away the story's potential biggest plot hole. By making her essentially afraid of her own sexuality (as exemplified by her horrified reactions to her intensely erotic dreams) it becomes possible to appreciate how she has been able to avoid any potential physical examination that would expose her strange mutation.

Though the cause of this mutation is most likely linked to the presence of the enormous nuclear cooling tower visible just a few miles from her house (as is the cancer slowing killing her mother) Lichtenstein’s script also suggests that it is a natural evolutionary step—one that is necessary if women are ever to wrest themselves from the physical dominance of brutal, sex-obsessed males.

If ever there was a subject begging to be exploited in a horror movie setting, Vagina dentata has to take first prize. While it has been used as a subtext (both consciously and accidentally) in many films, Teeth is one of the first to chuck metaphor out the window in favour of a direct representation of man’s biggest unspoken fear. It’s genius, though, comes in the way it allows us to subvert that fear and compels us to cheer on the young woman who is the unwitting symbol of primal emasculation. Rather than terrify us with a horrific descent into Dawn’s monstrosity, Lichtenstein chooses to create a story of empowerment in which Dawn’s mutation makes the slow transformation from inexplicable curse to exploitable gift.

Like Roth, Lichtenstein’s intentions are clearly satirical, which means its characters have been drawn to serve his thematic purposes rather than serve as three-dimensional representations of people found in our own non-cinematic reality. That said it does seem only fair that in a film where its female protagonist is partially defined by the devastating power of her vagina, all of the male characters are shown to be incapable of making any decision not immediately linked to the desires of their penises. In the world of Teeth, every male is a potential sexual predator, especially the nice ones who say all the right things.

I don’t mean to propagate the hoary old feminist cliché that every man is a wannabe rapist, but rather that the biological impulse to procreate remains strong enough that few men possess the inner-strength to ever completely disregard it. In Teeth this is best represented by the character Tobey (Hale Appleman), a fellow “abstainer” whose chaste flirtations with Dawn quickly escalates into violence as a result of his own pent-up sexual frustration (“I haven’t even jerked off since Easter,” he shouts at her in an attempted mitigation of his assault). During this, her first experience with intercourse, Dawn and Tobey both discover her hidden secret and following his entirely unexpected castration, he falls into the water they had been swimming in and does not come back up to the surface.

With this Dawn is not only forced to contemplate her mutation, but also her own sexuality for the first time in her life. This leads to her first ever visit to a gynecologist in a scene that best exemplifies the film’s darkly humourous tone. Perhaps it says something about my own twisted sense of humour, but I laughed longer and harder the first time I watched this moment than during any other scene I’ve seen this year.

With this second incident a clear pattern begins to emerge. Sensing Dawn’s unusual innocence, the men around her seek to exploit her sexual naiveté only to find out too late that they do so at their peril. Though she lacks the experience to immediately recognize the inappropriateness of the doctor’s actions (his gloveless probing clearly treading past the line from routine examination into outright molestation), subconsciously she identifies the violation for what it is and her body takes action against it. As will become clear with her next sexual experience, her strange “adaptation” does not act in opposition to her impulses, but directly with them. Though she does not know it yet, she is in complete control of her sexuality—it is merely a matter of accepting and embracing it.

Overcome by her role in Tobey’s death, the doctor’s mutilation and her mother’s collapse and subsequent hospitalization, Dawn finds herself drawn to Ryan (Ashley Springer), a boy from school whose crush on her has always been flagrantly apparent. He does his best to comfort her anxiety (including giving her some pills purloined from his mother), while also exploiting her duress for his benefit. He decorates his room with candles and gives her wine, having correctly identified the romantic tropes she associates with the abdication of her virginity. Touched by his gentleness and attention, Dawn engages with him in her first act of consensual intercourse and is shocked to find that when it ends he is none the worse for it. Afterwards she examines her topless body in the mirror and already a new self-confidence is apparent in her bearing and demeanor. In that moment she makes the visible transition from being a girl to becoming a woman, which makes what happens next all the more powerful.

About to leave, she is drawn back to Ryan’s bed for one more round of coitus, only to find out—via a phone call from his friend—that he has just successfully won a bet in which he would be the first to claim the pretty virgin’s maidenhood. In that moment the last vestige of her innocence is extinguished for good and Ryan promptly meets the same painful fate of Tobey and the bad doctor. Her reaction here is telling. No longer terrified of what she can do, all she can muster in way of a response is a comic “Oh shit,” as she dismounts Ryan and leaves him screaming in his bed. “Some hero,” she mutters to herself, having learned the truth behind her girlish romantic fantasies.

It’s interesting to note the degree to which the film allows its male "victims" to suffer. As a full-on rapist, Tobey’s punishment is death. The doctor, whose assault—while creepy—was not as violent or as obvious as Tobey’s is shown having his fingers reattached, but is also dramatically traumatized by the incident (“Vagina dentata,” he keeps repeating, “it’s real….”). Ryan’s initial tenderness is “rewarded” in that he survives the encounter and is—like the doctor—shown having his severed organ reattached to his body, although he too will doubtlessly be traumatized for life. Of them all it is her final “victim”—her stepbrother, Brad—who is punished with the worst of all the possible fates (at least from a decidedly male viewpoint).

Dawn’s opposite in every way, Brad’s callousness is the direct result of his resentment over the marriage of his father to Dawn’s mother. Not because of any lingering devotion to his own mother, but rather because of his feelings for Dawn. By making her his sister, the marriage prevented him from ever being able to act upon his sexual desire for her in a socially acceptable manner. For this reason when he hears his cancer-ridden stepmother collapse in the hallway, he ignores her cries and leaves her to be found by Dawn, who goes on to blame him for her subsequent death.

With this Dawn comes to realize that her “adaptation” is not a deformity, but rather an aspect of herself with which she can extract karmic justice. She goes on to visit Brad in his room, dressed for seduction (albeit in a manner that reflects her goodie-goodie instincts) and proceeds to deliberately do to him what she unintentionally did to the others. His suffering continues when Dawn defiantly drops his severed member onto his floor, only to watch as his pit bull escapes from its cage and proceeds to eat it in a couple of quick bites. Unlike Tobey, who didn’t live long enough to appreciate what had happened to him, or Ryan, whose mutilation was only temporary, Brad is shown being completely robbed of his manhood without any chance for recovery.

The film then ends with Dawn leaving her small town by hitchhiking out on the highway, And as much as I enjoyed everything that came before it, it is the film’s last scene that truly won me over. Trapped in the car with an obnoxious old pervert, Dawn is first annoyed by the situation, but that annoyance visibly dissipates when she realizes that she, not he, is the one who is truly in control of what is going on. Her smile at this awareness made me doing something I never do when I watch a movie—applaud. It was the only response I could think of to justify how good it made me feel.

Of all the films, Teeth is the most graphic in its depiction of its castrations. Though, unlike Hostel: Part II, we never actually see Dawn sever the penises from her “victims” bodies, we are exposed to much longer takes of the various aftermaths. Yet it remains the least discomfiting of the three films, largely because rather than acts of overt hostility, its castrations are presented either as an unconscious reaction to an assault or emotional betrayal or—in the last case—a just act of revenge committed against an utter douchebag. This is interesting in that it suggests that the power of onscreen violence has little to do with what we are actually shown onscreen but instead by how what we are being shown makes us feel. Though some would suggest this serves as a good argument in defense of restraint, one could easily argue with just as much validity that the degree to which graphic violence is acceptable depends on how the filmmaker intends their audience to react when they see it. In other words, it is foolish to suggest that one approach is better than the other when it all depends on the context in which they are used.

And that folks is my way-too-long look at a recent cinematic phenomenon only a freak like me would ever think to document. It only took me two months to throw it all together and I'm already fairly certain it wasn't worth the wait....